A Brief History of DNA Patents

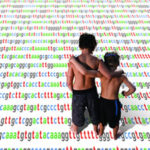

DNA holds information in a way that other biomolecules do not. Even discarding a blood spot or bit of spit doesn’t prevent telltale DNA sequences from living on in a database.

We regard our DNA data differently than we do, say, cholesterol test results. “Genes are uniquely ‘ours.’ They say something about us at some fundamental level, more than a mammogram or a Pap smear or an x-ray,” said James Evans, MD PhD, professor of genetics at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Our emotional attachment to our genomes may be part of why the patentability of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 cancer susceptibility genes has been pinging from court to court for years.

CERVIXES AND SPLEENS LED THE WAY

The two most famous cases of body parts exploited for profit –wild cancer cells and John Moore’s celebrated spleen – can’t match the power in the 3-billion-bit identifier that is a human genome. Even small pieces of the genome, combined with population frequencies, are powerful nametags, as the Supreme Court grappled with a few weeks ago in the ruling on expanded use of forensic DNA typing.

HeLa cells originated in the cervix of a poor, uneducated African-American woman. In 1951 Henrietta Lacks’s unusually prolific cells were sampled, cultured, and sent to labs all over the world, without her or her family’s knowledge. An HBO film will soon bring Rebecca Skloot’s book on this standard Bio 101 tale to life.

John Moore gave up his swollen spleen in 1976 to treat his leukemia, unaware that his physician, hospital, and a biotech company would patent the cells and sell an unusual protein that they produced. Moore sued, but the California Supreme Court ruled against him, finding that removed cells are not the equivalent nor the product of a person.

PATENTING LIFE, AND ITS PARTS

PATENTING LIFE, AND ITS PARTS

The U.S. Patent Act, passed in 1790, defined a patentable invention as novel, useful, and non-obvious to an expert in the field. It’s easy to see how a patent might apply to a toilet or Spanx, but the picture gets murky on the matter of DNA.

One can’t patent ideas, laws of nature, or products of nature. But it’s been okay to isolate a chemical from nature since Parke-Davis claimed adrenaline in 1911, deeming it different outside a body.

U.S. patent law infiltrated biology in 1980, with General Electric’s “oil eater” bacterium that combined DNA rings (plasmids) from four microbes. Nature hadn’t invented the combination, although the parts were out there in the wild. The oil eater is like inventing mixtures of peanut butter and jelly.

U.S. patent law infiltrated biology in 1980, with General Electric’s “oil eater” bacterium that combined DNA rings (plasmids) from four microbes. Nature hadn’t invented the combination, although the parts were out there in the wild. The oil eater is like inventing mixtures of peanut butter and jelly.

In 1990, the patent office added rules for claiming DNA sequences. Within a year, Amgen patented the first gene, erythropoietin (EPO), used to treat anemia and abused by certain famous athletes. The European Union declared genes patentable in 1998.

A gene’s DNA sequence minus the non-protein-encoding parts (the introns) renders it patentable, argued Myriad, for it’s no longer a “product of nature.” The court agreed that this complementary DNA becomes a novel “composition of matter.” It’s called “complementary” because it corresponds to the messenger RNA sequence that excludes the introns, not “composite DNA” as in the initial version of last week’s decision.

CANAVAN DISEASE WAS FIRST

An early gene patenting battle described in my gene therapy book was even more maddening than Myriad’s claims.

Canavan disease strips brain cells of their insulating myelin coating beginning in infancy and is usually lethal before adulthood. Canavan is one of the “Jewish genetic diseases,” but DNA doesn’t care in whom it mutates — anyone can inherit it. Affected kids who aren’t Jewish can have a tough time getting diagnosed when doctors consider religion first and genetics second (it happens). DNA Science recently explored the disease.

A genetic test is essential to confirm diagnosis of Canavan disease, because of shared symptoms with other leukodystrophies. The responsible enzyme isn’t normally in the blood, and a urine test is nonspecific.

In 1997, the patent for the Canavan gene sequence issued to four researchers and Miami Children’s Hospital, although labs were already using it. The hospital contacted all labs offering the test demanding that they stop, at a time when patient advocacy groups had finally gotten testing programs for the entire Jewish community – not just affected families – off the ground.

The hospital’s letter read, “We intend to enforce vigorously our intellectual property rights relating to carrier, pregnancy, and patient DNA tests,” supposedly to recoup the costs of developing the test – which was the work of a graduate student who was and remains horrified. He went on to become one of the leaders of the gene therapy field.

The cruelty of charging for the genetic test for Canavan disease was almost beyond comprehension. Parents who had donated their children’s brains to the researchers had to pay to test their other children!

Greenberg et al. v. Miami Children’s Hospital et al. was settled out of court when the plaintiffs ran out of funds, and as a result the test price fell and researchers became able to use the gene. Three years after the Canavan gene patent issued, in 2000, the first of Myriad Genetics’ BRCA patents issued. They’ve triggered outrage ever since.

The American Civil Liberties Union and the Association for Molecular Pathology, representing 150,000 geneticists, cancer survivors, pathologists, and others, sued the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), Myriad, and the University of Utah in May 2009. On March 29, 2010, senior judge Robert W. Sweet for the Federal District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled the patents invalid. Said he at the International Congress of Human Genetics in 2011, “A human gene is not an invention. DNA’s existence in an isolated form alters neither this fundamental quality of DNA as it exists in the body nor the information it holds.”

In August 2011 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit overturned Judge Sweet’s decision, and then the March 26, 2012 Supreme Court’s setting aside of that ruling kept the patent ball in play until the June 13, 2013 ruling against patenting the genes, but absolving their cDNAs.

With a fifth of the 20,325 or so human genes patented, and the cost and time to sequence a human genome or exome plummeting, the decision is important. With so many applications of the information in our genomes already here, the idea of owning a gene has been obsolete for some time. I’m glad that the Court has caught up with the science and plain common sense.

With a fifth of the 20,325 or so human genes patented, and the cost and time to sequence a human genome or exome plummeting, the decision is important. With so many applications of the information in our genomes already here, the idea of owning a gene has been obsolete for some time. I’m glad that the Court has caught up with the science and plain common sense.

Summed up James Evans, “the human genome is a shared legacy.” I couldn’t agree more.

(Exons of this post were published last year at Scientific American blogs, in an article I wrote in 1979 I forget where, in my textbooks, and in my teaching materials. Copyright law these days can be just as confusing as patent law!)

[…] PLOS Blog: A Brief History of Gene Patents […]

[…] or Spanx, but the picture gets murky on the matter of DNA. You can read the entire article here: A Brief History of DNA patents Reply With […]

[…] a number of cases it has been possible to narrowly avoid this rule by altering its interpretation [1]. The year 1911 saw the Parke-Davis company awarded a patent on adrenaline, by claiming it was […]

A quick question if two parents choose an alteration of DNA through mRNA and they have a child with the changed DNA

is the child subject to a patent.

mRNA doesn’t change DNA. It is a copy of sorts of DNA that is translated into protein in the cytoplasm.