A Checklist for Gene Therapy From the UK Cystic Fibrosis Trial

Washington, D.C. I’m at the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy annual meeting, one of my favorite conferences. The very first talk provided a great example of why it is taking gene therapy so long to reach the clinic — a milestone that hasn’t happened yet in the U.S. The first gene therapy experiment was 24 years ago.

For the first talk, Uta Griesenbach, PhD subbed last minute for Eric Alton, MD to present progress in a phase 2b double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of gene transfer (that’s what gene therapy is technically called before results indicate it works) to treat cystic fibrosis (CF). It’s “wave 1” of the effort from the UK Cystic Fibrosis Gene Therapy Consortium, in which more than 80 researchers are participating.

The consortium made headlines about two years ago when the UK Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research refilled their coffers with £3.1 million (US$4.9 million). Funding had been dwindling, perhaps because of the physiological hurdles that CF presents, against the backdrop of gene therapy setbacks. These began with the death of 18-year-0ld Jesse Gelsinger in 1999 days after gene therapy, and the leukemia that’s cropped up in clinical trials for two immune deficiencies. Many investigators had given up on gene therapy for CF – but not the tenacious UK group, led by Dr. Alton.

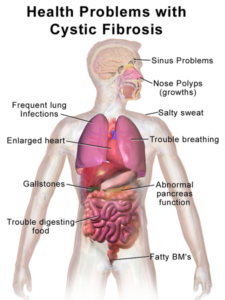

Cystic fibrosis, at the risk of evoking clichés, has been a tough nut to crack. The gene and its encoded protein, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), were discovered in 1989, and my post from April 10 details some of the earlier history of this disease.

The multi-system symptoms – lung congestion and susceptibility to infection, pancreatic insufficiency, male infertility – result from malformed, misfolded, or absent chloride channels. More than 25 clinical trials, involving more than 400 patients, have attempted to deliver functional CFTR genes.

Improvements were limited or transient, because of the nature of the illness. Thick sticky mucus gets in the way, and cells lining the respiratory tract divide so often that normal cell turnover may jettison an altered cell in a cough or swallow too soon to see a sustained effect. Plus, correcting the problem in the airways won’t alleviate the pancreatic clogging that leads to the classic symptom of “failure to thrive.”

Most gene therapy trials use retooled viruses as vectors to deliver the payload, but wave 1 delivered CFTR genes in an aerosol of tiny lipid bubbles, liposomes. They echo the lipid bilayer of a cell membrane so coalesce themselves across that barrier, releasing their cargo inside.

At first I was disappointed when Dr. Griesenbach said she wouldn’t be presenting results. But when she explained why – “we haven’t broken the blinding yet” – I suddenly realized that the journey to demonstrating that a new therapy works is just as interesting as arriving at that destination.

A double-blind, placebo controlled trial design may seem cruel, intentionally depriving people of a possible treatment, but it is essential to demonstrating that a new treatment actually works. There are workarounds – the control group can receive an existing treatment. And trials are revamped, access expanded or FDA approval accelerated if a result is obviously compelling and people are suffering. The cancer drug Gleevec is an example of a drug hurtling towards the market. It happens, but very rarely.

I don’t think Dr. Griesenbach intended to focus on the hurdles researchers must leap to even plan testing a gene therapy, but that’s what held my attention. The reasons help to explain why clinical trials can take years. Following are the questions that needed answers and the concerns that emerged during this CF trial, which has been in progress since 2002.

1. How much of a gene’s function must gene therapy restore?

In gene therapy, a small change can go a long way. That’s the case for a gene transfer approach for the clotting disorder haemophilia B, presented at a news conference by Andrew Davidoff, MD, from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Introducing the gene for clotting factor IX that restores the level to less than 8% of normal activity can free a man from needing to take clotting factor to prevent life-threatening bleeds.

For CF, men whose only symptom is infertility have 10% residual function of the chloride channels. “So if we can achieve some increase, we can have a significant impact,” said Dr. Griesenbach. A 6% increase in lung function might be all that’s necessary.

2. How should researchers pick the best vector and its cargo?

Choosing a vector and making it safe is perhaps the toughest challenge in gene therapy. Investigators must design the delivery method before a phase 1 trial gets underway, and stick to it.

The situation isn’t like getting a new laptop when Apple introduces a new and improved model. Researchers can’t change or tweak a virus, alter the recipe for a liposome, or replace the DNA cargo without going back to square 1, phase 1. It’s one reason why the gamma retroviral vectors that caused leukemia and the adenoviruses that evoked a devastating immune response are still in use, although some have been made “self-inactivating.”

The CF trial used a liposome delivery method developed at Genzyme awhile ago. But the researchers modified the DNA within to decrease the stretches of cytosine and guanine (“CpG islands”) that invite inflammation and they added a bit to extend the effect. That meant starting from scratch in the phase 1 trial, even though the liposome recipe had been used before.

3. Which endpoints are the most meaningful?

The CF team tests cells lining the nose and airways for chloride transport, finding that it can reach about 20 percent of normal following gene transfer. Other assays include a “lung clearance index” from inhaling a harmless dust and scans that use technetium to show clear areas in the lungs.

But these measures meant little to the trial participants. “The patients said, ‘so what? Will it make my lung disease any better?” Dr. Griesenbach said. “Our program is now hinged around addressing that question. How much improvement is necessary to have a clinical effect?” A quality-of-life questionnaire is now part of the protocol.

4. Which types of patients should a clinical trial enroll?

Should the sickest patients try a new treatment because they are the most desperate, or should the healthiest, because they have a better chance of surviving the experiment? Part of the outcry over the death of Gelsinger that effectively halted the field for two years was the fact that he had not been desperately ill.

The symptoms and natural history of CF dictate the optimal age of trial participants. “In CF we face a dilemma. Very young children have less mucus, but it is harder to measure their increase in lung function. In the full-blown disease patients have lots of thick sputum. It is hard to find the right patients. You need a balance,” Dr. Griesenbach said. They decided on 12 as the minimum age, with average age 22.

Patients received 12 monthly doses, bracketed by 4 additional visits, and the last participant finished just two weeks ago. The monthly intervention was nothing compared to the hours of procedures that people with CF go through on a daily basis to expel mucus.

I don’t know whether the patients in the UK trial are stratified by mutation, but the development of the blockbuster drug Kalydeco illustrates the importance of distinguishing among the 1600 or so variations of the CFTR gene sequence. Kalydeco corrects misfolding, which affects only some patients with specific mutations, but can be teamed with other drugs to help more. And a new contender for a CF drug is targeted at patients with nonsense mutations, who make no CFTR protein at all.

5. Expect the unexpected.

The researchers determined that they needed 120 patients, and they started with 130, just to be safe. Then in January 2012, the FDA approved Kalydeco. Some participants, understandably, dropped out of the liposome gene transfer study to take the new drug.

6. Think ahead.

So far, CFTR delivery via liposomes seems to be safe. Some of the patients who are feeling better baked cakes for the researchers, although efficacy isn’t known yet. But the consortium is running a parallel “wave 2” using lentivirus (disabled HIV), in case the fatty bubbles aren’t efficient enough or the effect too transient. (I’ll cover HIV as a gene therapy vector in a future post.)

Results are in, Dr. Griesenbach concluded, and will be presented at the North American CF Conference in October. So far the team knows that patients experience a very brief period of fever and decrease in lung function, but recover well. Then some of them improve. A third of patients fully responded, another third had some correction of lung function but not to entirely normal levels, and a third didn’t respond.

The unblinding will reveal whether the gene transfer is responsible for the patients who did the best. And if they are indeed the ones who received functional CFTR genes, then the next chapter – a phase 3 trial – will be up to industry.

It’s easy to see why approval of a gene therapy takes so long!