COVID-19 Vaccine Will Close in on the Spikes

As epidemiologists try to stay ahead of the spread of new coronavirus COVID-19, vaccine developers, like Sanofi and Johnson & Johnson, are focusing on the “spike” proteins that festoon viral surfaces. Following clues in genomes is critical to disrupting the tango of infectivity as viruses meet and merge with our cells.

Vaccine developers look specifically to the molecular landscapes where viruses impinge upon our respiratory and immune system cells. Targeting COVID-19 is especially challenging, because efforts to develop a vaccine against its relative, the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV), elicit only partial responses. But those steps are now serving as jumping off points for pharma.

The relationship between viruses and humans can seem like a science fiction plot. The viruses that make us sick may be little more than snippets of genetic material borrowed, long ago, from human genomes. Packaged with their own proteins, viruses return to our bodies, taking over to make more of themselves.

A zoo of animal hosts

Coronaviruses present a “severe global health threat,” write researchers from Wuhan University and Sun Yat-sen University in the Journal of Medical Virology. The viruses aren’t new, nor do they infect only people. They cause:

- diarrhea in pigs, dogs, and cows

- fever and vasculitis in cats

- fever and anorexia in horses

- severe lung injury in mice

- lung disease and death from liver failure in whales

- respiratory tract infection in birds (bulbuls, sparrows, and chickens)

Some species spread coronaviruses without becoming sick, like the camels that carry MERS, and bats, which carry many viruses.

Human Coronaviruses Before COVID-19

Before December 2019, six coronaviruses were known to infect humans. The first two, HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43, were discovered in the 1960s. They cause about 30% of colds, with rare case reports of pneumonia in patients who had other viral infections or were immunocompromised.

In 2002 came SARS-CoV and in 2004 HCoV-NL63, which causes pneumonia and bronchitis, rarely. SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) caused more than 8,000 infections and 774 deaths, but most of us have antibodies to NL63, indicating past exposure that didn’t make us very sick.

In 2005 came HKU1. It causes pneumonia in young children and 1.5% of cases of adult respiratory distress syndrome.

MERS-CoV (Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome) emerged in 2012 in the Arabian peninsula, and is rare but can be fatal. SARS and MERS show zoonotic (to other animals) as well as human-to-human transmission.

Two coronaviruses without a predilection for human bodies may also be important, epidemiologically speaking. HKU2, which killed 24,000 piglets in southern China from diarrhea in 2017, is the first “spillover” from a bat coronavirus to livestock. And Beluga whale CoV/SW1, although only distantly related to the human pathogens, could reveal how bat viruses get into sea creatures.

The coronaviruses are of four genera (equivalent to the “Homo” in “Homo sapiens”): alpha, beta, gamma, and delta. COVID-19, SARS, MERS, HCoV-OC43, and HKU1 are beta. Two other human coronaviruses, HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63, are alpha.

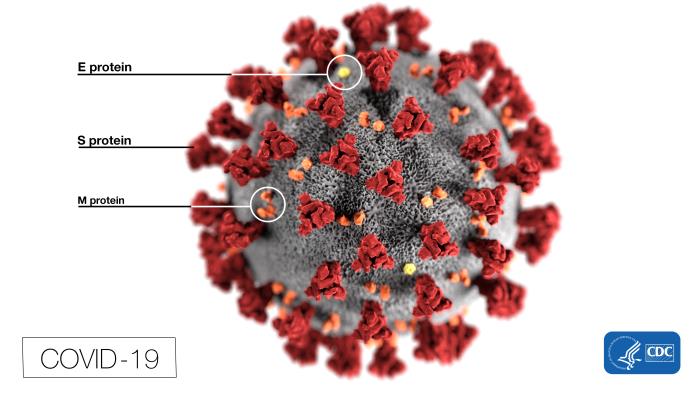

Anatomy of COVID-19

A virus isn’t a cell, isn’t even considered alive. It’s a nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) wrapped in a coat of proteins, some attached to sugars (glycoproteins).

Many familiar viral pathogens – those that cause cold, flu, hemorrhagic fevers like Ebola, rabies, dengue, and yellow fever – are RNA viruses, notorious for mutating rapidly and unable to correct errors.

The “body” of COVID-19 is basically a genome enveloped in glycoproteins, with a smear of fat and bearing the crown of spikes that inspired the name “coronavirus.”

The genome is a single strand of RNA that is termed “positive-sense.” That means that the infected cell treats the viral genome as if were it’s own messenger RNA (mRNA), translating it into proteins. A “negative-sense” RNA virus requires more manipulation; a host enzyme must make a positive-sense copy.

A coronavirus genome typically is 26,000-32,000 bases long. That’s hefty for a virus, but tiny compared to a human gene. Our BRCA1 gene, for example, is 125,951 bases long. Coronavirus RNAs are embellished with “caps” and “tails” like those of human mRNAs.

Once ensconced in a human cell, a half dozen or more viral mRNAs are peeled off. The first, representing about two-thirds of the viral genome, encodes 16 protein “tools” that viruses require to replicate. Making this toolkit is a little like downloading an installer for new software.

Once ensconced in a human cell, a half dozen or more viral mRNAs are peeled off. The first, representing about two-thirds of the viral genome, encodes 16 protein “tools” that viruses require to replicate. Making this toolkit is a little like downloading an installer for new software.

The tools (“non-structural proteins”) are enzymes needed to produce the other encoded proteins, and transcription factors to continually renew the RNA instructions.

The other third of the viral genome encodes four “structural” proteins that are the nuts and blots that build the virus:

- Spike, or S protein, is made early in infection. One part of it, S1, grabs a receptor molecule sticking out of a host cell and another part fuses to the cell membrane. Three copies of the S protein form each spike.

- Membrane (M) glycoprotein lies beneath the spikes, where it shapes mature viral particles and binds the inner layers.

- Lipid (fat) is borrowed from host cell membranes during past infections.

- Envelope (E) glycoproteins control the assembly, release, and infectivity of mature viruses.

- Nucleocapsid (N) proteins knit a characteristic shell of identical subunits, like the panes of a greenhouse, that binds and packages the RNA genome. It also serves as a cloaking device, hiding viruses from our immune system’s interferons and RNA interference.

All coronaviruses share the “tools,” but differ in a few additional structural proteins tailored to the host species.

COVID-19’s Spikes Bind at ACE2 Receptors

Viruses have co-evolved with us, using proteins that jut from our cell surfaces. HIV and West Nile virus enter through CCR5 receptors, which dot white blood cells. Influenza viruses bind sialic acid residues. Coxsackievirus and adenovirus target part of an antibody. And herpes simplex uses 3 different doorways.

COVID-19 latches onto angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, aka ACE2.

To us, ACE2 is an enzyme that has an effect on blood pressure.

To COVID-19, ACE2 is a receptor, an entranceway, in the airways and alveoli (air sacs) as well as in blood vessel linings. ACE2 is also a receptor for SARS-CoV and NL63-CoV. (MERS-CoV uses a different receptor.)

The key to developing vaccines and treatments is the three-dimensional shapes of the parts of the virus that contact our cells.

SARS and NL63-CoV bind to a helical part of ACE2 that snakes up from cell membranes, forming distinctive tunnels and bridges that comprise a “hot spot” for viruses. The attraction of a virus to a cell receptor hot spot is a little like a tired commuter emerging from a subway station and seeing a Starbucks sign, moving towards the coffee shop as if dragged by a tractor beam. The viral hot spot that beckons both SARS and COVID-19 is a shared drug and vaccine target – and so all the work on developing a SARS vaccine is now in the spotlight.

Researchers knew from SARS that the S1 parts of the viral spikes hug the ACE2 receptor at a region of five amino acids (protein building blocks). Even though four of the amino acids differ in COVID-19, they are similar in size and charge to their counterparts in SARS.

If S1 attaches SARS to the ACE2 receptor like a boat docking, would COVID-9 tie up at exactly the same points?

Teaming a traditional crystal structure approach with computational methods, Pei Hao, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and colleagues modeled the interface, showing that COVID-19 indeed binds ACE2 just like SARS does, with slightly less force. In a Letter to the Editor of Science China Life Sciences, they conclude that the new virus “poses a significant public health risk for human transmission via the S-protein-ACE2 binding pathway.”

Even more recently, researchers from the University of Texas at Austin and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease used electron microscopy to zero in on a “pre-fusion” spike protein triplet nearing the receptor. They imaged one of the three spikies rotating upward to latch onto the receptor, revealing precisely where a vaccine must fit. The work is published in Science.

A Fish, A Bat, and A Human Walk Into a Seafood Market …

Comparing genome sequences is a classic way to sort out evolutionary relationships, and the comings and goings of viruses are evolution in action. Evolutionary trees, whether going back millions of years to dinosaurs or just years to viruses, depict descent from shared ancestors. The meme of chimps leading directly to humans is and has always been incorrect.

COVID-19 and the SARS-CoV have a common ancestor, a bat coronavirus. But COVID-19 is actually closer to the bat virus, sharing 96% of its genome sequence, compared to about 86% with SARS-CoV. And muddying the waters further, COVID-19’s spike gene shares a 39-base insertion with a type of soldierfish that swims in the South China Sea.

Somehow, the virus that evolved into COVID-19 may have started in a bat in 2013 and gotten into fish that ended up in the Wuhan Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market at the epicenter of the pandemic.

The confusion arises from the promiscuity of RNA viruses. Over the ages, they swap genetic material, mutate, and lose and gain pieces of themselves. The result is a constant spawning of patchwork genomes that under some circumstances harm the host species. And our bodies help it all along, sneezing, oozing, bleeding, or crapping out zillions of viruses before either expiring or recovering.

Did COVID-19 Come From Us?

How does a virus find itself at a door to a host cell? The “escaped gene” hypothesis leads the classic list of three explanations for a virus, such COVID-19’s, emergence:

- Viruses were ancient intermediates between collections of self-replicating chemicals and the first cells. (The virus-first or primordial viral world hypothesis).

- Viruses were once cells invaded by parasites that robbed them of the ability to manufacture their own proteins. As viruses, they infect cells to make the proteins they need to reproduce. (The cellular regression hypothesis)

- Viruses evolved, many times in many organisms, as mobile genetic elements – aka “jumping genes” – that produced protein coverings and took bits of fatty membrane from cells. (The escaped gene hypothesis).

All three may have happened.

So what’s COVID-19’s story? Is a hint in what normally binds the receptor?

Perhaps sometime in the past, a virus formed, or came to include, human DNA or RNA instructions for making an integrin, which is a protein that binds to ACE2. Integrins glue our cells to surrounding connective tissue. The viral spike masquerades as the integrin, grabbing our cells.

In other words, a viral epidemic may arise as an accident, of sorts, of biochemistry and evolution.

Vaccine!

Spike protein took center stage as a vaccine candidate early in the SARS outbreak, because it elicits an antibody response in mice. Various vaccine strategies – live weakened SARS, hitching spike genes to existing vaccines, circles of DNA housing spike genes and triplets of spike proteins in nanoparticles – haven’t worked well enough. But genomic technology has exploded since SARS, leading to insights with astonishing rapidity.

In an exhaustive study preprinted in bioRxiv, Arunachalam Ramaiah of the University of California, Irvine and Vaithilingaraja Arumugaswami of UCLA catalogued where key parts of the four structural proteins of COVID-19 bind to the proteins that mark immune system cell surfaces. The work implicated the spike protein, but from the perspective of the immune response rather than the receptor.

Now pharma and biotech companies are charging ahead to create vaccines, partnering with BARDA, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority. Under Health and Human Services, BARDA was established in 2011 “to aid in securing our nation from chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats, as well as from pandemic influenza and emerging infectious diseases,” by speeding the trajectory of diagnostic, vaccine, and treatment development.

But vaccine and drug development take time. Until then, treatment remains supportive. Meanwhile, epidemiologists are filling in the denominators of the case:fatality stats to determine exactly how deadly the infection is, and assess if asymptomatic individuals are unwittingly spreading it.

I’ll end with a sobering thought from a pathogen’s point of view. Even if we vanquish COVID-19, a continuing if not escalating perfect storm of events foreshadows other viral epidemics: climate change, human travel, and our encroachment into the turfs of other animals.

I think this sentence is wrong:

“ACE2 is an enzyme that converts the hormone angiotensin I to angiotensin II, which constricts blood vessels, raising blood pressure.”

You might have confused ACE2 with ACE.

ACE2 is the enzyme that converts Angiotensin-II to Angiotensin 1-7, a vasodilator. So basically ACE2 counteracts the effects of ACE.

Thanks Alexander. I am confused over this point, and hope that you can explain it better than I did. Here is one of my sources: “Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14647384. That headline sounds to me as if the enzyme is the receptor – which isn’t how I’d envision an enzyme. Can you explain it better? Thank you!

Also, I am seeing use of 2019-nCoV as the name, so perhaps it is still in flux. I’ve always read it called SARS-2, which I believe is incorrect.

Thank you!

thank you for the post

Thank you! It’s difficult to keep up, but I like to explain how things work.

The sentence causing confusion only works in context. The key word, as it relates to the confusion, is “functional”. The point of this confusing title is that the SARS binding site interacts with the ACE2 binding site. The fact that ACE2 is also an enzyme is beside the point as far as the virus is concerned. The availability of the ACE2 binding site on the membranes surface is the point.

This connects to your later reference to the binding of ACE2 with an integrin. Similarly, the integrin/ACE2 interaction presumably uses the enzymatically functional ACE2 binding site, but the molecular interaction does not serve an enzyme/substrate reaction, it serves a cell/cell interaction.

You have written a very fine report on a complex, fast breaking story. We are all trying to keep up.

Exactly! The fact that ACE2 is an enzyme to us IS beside the point – it’s a receptor for the virus. Thank you for explaining it so clearly!

Interesting… Is it possible to produce a substance that outcompete virus at ACE2 binding site? Or at least modify it sufficiently to reduce virus adherence? Maybe it could be developed from virus own RNA spike proteins code? Then infection of subsequent cells should slowdown due to lack of responsive ACE2 and host would have more chance/time to cleanup itself from virus…

I’m just curious…

Yes Radek, that’s the idea, as far as I know. Perhaps a small molecule library might yield a candidate drug with the correct conformation to block the receptor. Several companies are working on this, and work had been done on SARS that may be applicable because the two viruses target the same receptor. It’s fascinating that related viruses can target different receptors. Thanks for commenting.

The virus binds via surface receptors and penetrates inside the cells.

can corvid19 receptors be blocked by other viruses that are less infectious?

I don’t know — sounds like a great idea. Can anyone provide more info?

Thank you for this! Very well written, with hints of humour and elegant explanations.

Thank you so much! Made my day. I am grateful to Public Library of Science for providing me with a weekly forum to explain how science works.

franciscaleb403@gmail.com

It was a great article, right up until you closed with the obligatory genuflection to climate change.

Climate change alters habitats and that could affect viral transmission patterns. We just don’t know enough yet.

Alexander couldn’t have been much clearer.

You are wrong in regards to the function of ACE2. As Alexander said above, you mistook the function of ACE2 by saying it’s an enzyme that converts AngI to AngII. ACE2 actually converts AngII to Ang(1-7). ACE converts AngI to AngII.

The binding of AngII to AT1 Receptors causes vasoconstriction (elevates BP), among other effects. AngI –> (ACE) –> AngII –> AT1 Receptors –> vasoconstriction. Therefore, ACE ultimately leads to vasoconstriction/high BP.

The binding of Ang(1-7), which is a product of the interaction of AngII and ACE2, to mas Receptors causes vasodilation (lowers BP). AngII –> (ACE2) –> Ang(1-7) –> mas Receptors –> vasodilation. Therefore, ACE2 ultimately leads to vasodilation/depress BP.

Ergo, ACE and ACE2 have opposite effects.

ACE2 is a protein, and proteins have many functions. ACE2’s dominant and most well-known function is acting as an enzyme (causing AngII to convert to Ang(1-7)). However, it also can act as a virus receptor. In healthy human physiology, ACE2 acts as an enzyme (often embedded in a cell membrane): AngII binds to the active site of the enzyme, a series of catalytic reactions occur, and Ang(1-7) is produced, causing it to dissociate from the enzyme and exert its function elsewhere at mas Receptors. In human-viral pathophysiology, a viral particle binds to an alternative residue on a membrane-embedded ACE2 (distinct from the active site in the case of COVID19) which causes the cell (i.e. the cell in which the ACE2 is membrane-bound) to internalize the viral particle. Therefore, the membrane-embedded ACE2 has functioned as a receptor, rather than an enzyme. Tldr; it’s not a receptor in the “traditional”/healthy respect aka endobiotic substances do not (usually) activate it as a receptor; but in a pathogenic state, xenobiotic substances can cause it to unusually act as a receptor.

Kind of shocked you have your PhD in genetics and are an author of life science textbooks, yet you got the basic RAS pathway wrong and could not understand ACE2 as a receptor… pretty sure I learned that in high school biology. If you still don’t understand: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9BYF1#function, and google image search “RAS pathway”.

Thank you for the clarification.

One observational note is the fact that through the Epidemiological Characteristics and the comorbidities presented in fatality cases (http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e53946e2-c6c4-41e9-9a9b-fea8db1a8f51) the hypertenion group had a significantly high rate of deaths. That may indicate something !

Maybe the connection of SARS 2 Cov to ACE2 leads to reduction of Ang-II levels and Additionally, and independently may have something to do with the elevated death rates

BP is under estimaded by the population so in the subbgroup of non reported comorbidity maybe is the missing point !

One way is to find the vaccine the other is to minimize the deaths by managing the danger

Some thoughts that i shared with you loudly

So researchers know how many spike proteins are present on the surface? I’ve seen images of the virus, but no one has quantified the number. Can you please provide some insights?

Good question. I couldn’t find it in current papers nor in the SARS literature – does anyone know?

I have hypertension and use an ACE inhibitor. Is there any information on whether or not this is harmful or beneficial in cases of contracting COVID-19?

Here’s an article on this: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32061198 It suggests ACE inhibitors may be useful. The final sentence of the abstract: “Therefore, we speculate that ACEI and AT1R inhibitors could be used in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia under the condition of controlling blood pressure, and might reduce the pulmonary inflammatory response and mortality.”

Great question! You should ask an MD for more info.

this is something new, you going to be a bitch to someone who is trying to explain to laymen what is going on? stupid

Thank you so much, Stacy. I was going to comment back at Kika slamming me but thought I’d be the adult in the room. He/she may know biology better than I do, but hasn’t a clue about what science journalism is. Sometimes you have to boil things down, and yes, sometimes I don’t understand something. Trashing someone on her blog is inappropriate and juvenile. You made my day!

Mrs Lewis, PhD, really many thanks that you are writing this so famous issue by courage. Before critisism first we must applause this article. Sure, there are many unknown things that’s why this discussions are very interested. From the discussions interestgly I found there are two forming points that can give some chances to fight with this virus:

1) to prevent ACE2 connection with the virus in any way ; how can be possible? Is there mechanism to reduce, eleminate ACE2 without causing problem to the organism? I heard that some people even can not have this ACE2 at all, is it true?

2) to infect ACE2 with another virus so to occupy ACE2 in advance and not leave empty space ; it seems so radical measure but which less dangarous virus can do this?

And as 3th way I think, what about to see how bat can host this virus by not been sick how bat’s immune system is working or is there any antibody that keep this virus safe in the bat? What is the mechanism there? If this can be copied/replicate to human immune system?

I will be very thankful to hear your comments even as short answers. Also other commentators’ opinion in the forum are welcomed..

Mrs Lewis, PhD, really many thanks that you are writing this so famous issue by courage. Before criticism first we must applause this article. Sure, there are many unknown things that’s why this discussions are very interested. From the discussions interestingly I found there are two forming points that can give some chances to fight with this virus: 1) to prevent ACE2 connection with the virus in any way ; how can be possible? Is there mechanism to reduce, eliminate ACE 2 without causing problem to the organism? I heard that some people even can not have this ACE2 at all, is it true? 2) to infect ACE2 with another virus so to occupy ACE2 in advance and not leave empty space ; it seems so radical measure but which less dangerous virus can do this? And as 3th way I think, what about to see how bat can host this virus by not been sick how bat’s immune system is working or is there any antibody that keep this virus safe in the bat? What is the mechanism there? If this can be copied/replicate to human immune system? I will be very thankful to hear your comments even as short answers. Also other commentators’ opinion in the forum are welcomed..

Anton, thanks. Here’s an article I posted 2 weeks ago that gets into the bats, towards the end, with a link that might help.

Oops forgot the link: https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2020/02/11/will-scientists-ever-get-ahead-of-fast-mutating-deadly-health-viruses-exploring-the-coronavirus-and-the-genetics-of-other-plagues/

Thank you, Dr. Lewis!

Thank- you for the post and I apologize for the rudeness of the one commenter. And the mention of climate change is critical in this discussion. I remember when pharmas were closing drug discovery and development departments, both basic and applied research, with the idea that anti-infectives were no longer required. Very little awareness there about zoonoses, cross-species transmission and emergence. Now we are dealing with the consequences.

Any comments on the researcher in Taipei’s theory? “Given China’s poor track record with lab safety management, the virus is likely to have escaped from a facility,” public health researcher Fang Chi-tai said In article dated February 23, 2020:

http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2020/02/23/2003731479

Any word on ACE2 receptor variants susceptibility to COVID-19?

Or ACE2 receptor variants distribution of deaths and recoveries?

I don’t know. But, I’ll admit I did wonder why COVID-19 is so closely related to that other coronavirus (not SARS), more closely than it is to SARS and MERS. I love science fiction about outbreaks, but I would so hate for this to be true. Thank you for posting the link!

I don’t know, I can’t keep up! The post you read, I rewrote it 3 times in one hour and then finally gave up on staying current. And I’ve never written “I don’t know” so many times and I’ve been a science writer a very long time. I wonder on the variants too. Also, are folks who regularly take ACE2 inhibitors protected? I suppose we’ll have to wait a bit and then do the epidemiology on that. Thanks for writing!

A friend contacted me to say he’s writing a paper right now about the influence of climate change and the epidemiology of COVID-19, so it is relevant. As for de-funding basic research and the short-sightedness of this, a certain president cut funding to the CDC not so long ago. There’s widespread little awareness about life science, any science, in general. As for the incredibly rude comment, it seems that person needed an ego stroke by bashing me. The best response is to ignore it. This one may have been the most obnoxious I’ve ever received. Thank you for your support!

Sometimes the best response is “I do not know”. Often times the PHD or MD after the name lends more weight to the words that follow than may otherwise be warranted.. “I do not know” liberates one from some of the burden the title may bestow.

ACE2 receptor binding site is an interesting connection, remember that this is NOT the same as ace-inhibitors please be very careful, it would be terrible for a connection to be made without the appropriate data.

” In contrast to ACE, ACE2 activity seems to be unaffected by classical ACE inhibitors given distinct substrate-binding pockets [3]. Interestingly, increased cardiovascular expression of ACE2 and plasma Ang(1-7) levels have been demonstrated by treatment of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) as well as mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) in animals and humans [10-12]. Several other roles of ACE2 have been described in the literature including the modulation of the integrin signaling pathway [13, 14] and interaction with the apelin-APJ pathway [15]. In the absence of ACE2, increased plasma and myocardial Ang-II levels have been attributed to reduced metabolism of plasma Ang-II [16, 17]. ”

The only known pharmaceutical information I have come across concerning ACEII is associated with the Angiotensin II receptor blocker so called ARBS.

“Interestingly, increased cardiovascular expression of ACE2 and plasma Ang(1-7) levels have been demonstrated by treatment of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) as well as mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) in animals and humans [10-12].”

We need more detailed case reports on patients.. We need to know the medical history and medication history of the patients.. I believe this information would inform and prepare our population.. We also need data that describes quantitative gene level expression of ACE2 receptors in the context of chronic ARB treatment and chronic hypertensives vs nonsensitive.

The impact of drug therapy on directly modulating ACE2 activity and expression has not been well described. In the setting of acute decompensated HF in patients with advanced HF, circulating s ACE2 activity was found to increase following intensive medical therapy aiming to optimize hemodynamic derangements and relief congestion [1]

1.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3944399/

2. Shao Z, Shrestha K, Borowski AG, et al. Increasing serum soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity after intensive medical therapy is associated with better prognosis in acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2013;19(9):605–610.

10. Keidar S, Gamliel-Lazarovich A, Kaplan M, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor blocker increases angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity in congestive heart failure patients. Circ Res. 2005;97(9):946–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Simoes e Silva AC, Silveira KD, Ferreira AJ, Teixeira MM. ACE2, angiotensin-(1-7) and Mas receptor axis in inflammation and fibrosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169(3):477–492. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Zhong JC, Ye JY, Jin HY, et al. Telmisartan attenuates aortic hypertrophy in hypertensive rats by the modulation of ACE2 and profilin-1 expression. Regul Pept. 2011;166(1-3):90–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Lin Q, Keller RS, Weaver B, Zisman LS. Interaction of ACE2 and integrin beta1 in failing human heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1689(3):175–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Sato T, Suzuki T, Watanabe H, et al. Apelin is a positive regulator of ACE2 in failing hearts. J Clin Invest. 2013 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Zhong J, Basu R, Guo D, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 suppresses pathological hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis, and cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2010;122(7):717–728. 718 p following 728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Kassiri Z, Zhong J, Guo D, et al. Loss of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 accelerates maladaptive left ventricular remodeling in response to myocardial infarction. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(5):446–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] *Important demonstration of the cardioprotective role of ACE2

Thank you Dr. Gargiulo. My intent in the 3 articles I’ve written about COVID-19 is to educate the public about what viruses are, where they may have come from, and how they infect. The unspooling information rapidly became over my head and I’m quite willing to admit that. I did my PhD on flies with legs growing out of their heads! COVID-19 is an evolving situation that requires expertise from several areas, and as you write, more detailed case reports on patients are imperative. Thanks you, especially for the reference list. I will dig in.

Thank you very much Riki,

It’s very seldom someone tells us the truth AND their limits. Your input is very valuable to me. Thanks from an Engineer just trying to understand : )

Thank you for your comment. New readers can refer to the excellent comment stream, and I thank all who have contributed.