Complex Controls to Make a Mouse Limb

The cover of the June 7 issue of Science excited me in the way that the title of a summer beach read might excite a normal woman. One word – morphogenesis – looms over a landscape of what look like pink starfish, but are in fact tiny bits of small intestines, blooming from individual starter stem cells. Inside I found a list of articles about development that made me toss aside the fiction issue of The New Yorker. I went straight to the article on homeotic mutations.

In my former short life as a scientist, I was immersed in the world of homeotic mutants, which have their parts in the wrong places. I worked with fruit flies, but all manner of multicellular life forms have homeotic mutations, from frogs to flowering plants.

My flies had legs on their heads and antennae snaking from their mouths. Homeotic mutations cause diseases in people too – a form of leukemia in which blood lineages switch, lower jaws that are really upper jaws, and arms that are really legs .

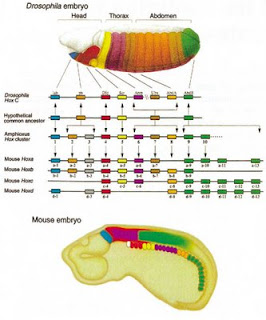

As mutants tend to do, the homeotics teach us what happens normally, but with a special twist that drew me to devote my PhD years to them: the genes that control the sequential formation of body parts are themselves laid out in the exact sequence along the chromosome in which they are deployed as development proceeds.

Back in grad school at Indiana University, in Thomas Kaufman’s lab circa late 1970s, we’d gather every morning at a chalkboard and take turns drawing the sequence of homeotic genes on chromosome 3 and the parts of the fly embryo that they oversee. In those pre-genomic days, we thought the homeotic or “Hox” genes of the Antennapedia complex controlled each other. Why else would they be aligned in the precise order of their use, like lining up clothing for different kids getting ready for school?

Back in grad school at Indiana University, in Thomas Kaufman’s lab circa late 1970s, we’d gather every morning at a chalkboard and take turns drawing the sequence of homeotic genes on chromosome 3 and the parts of the fly embryo that they oversee. In those pre-genomic days, we thought the homeotic or “Hox” genes of the Antennapedia complex controlled each other. Why else would they be aligned in the precise order of their use, like lining up clothing for different kids getting ready for school?

We brainstormed. We hypothesized. But we could barely guess at how these weird genes, in their normal forms, know how to do what they do. And that was the fun of science back then – looking at sparse (by comparison to today) data and trying to figure out what was happening, what the underlying mechanism was that laid out the pattern of body parts in a plant or animal.

The paper in the June 7 Science, “A Switch Between Topological Domains Underlies HoxD Genes Collinearity in Mouse Limbs,” reveals that our conjecturing around the chalkboard so long ago was much too simplistic. The work, from Guillaume Andrey, a doctoral assistant, professor Denis Duboule, and others at Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, focuses on the HOXD cluster in mice that specifies limbs. It turns out that the sequential genetic instructions are used more than once as development refines the initial bud into a forelimb or hindlimb, and some of the controls come from outside the gene complex.

First a wave of homeotic gene activity establishes the body axis. The controls of this initial action lie in “gene deserts” that flank the HOXD gene cluster, so-called because protein-encoding genes are few and far between. The initial control turns on the neighboring HOXD genes by parting the chromatin proteins that shield the genes. Once accessed, the HOXD genes instruct the cell to make protein transcription factors that, in turn, control other genes that sculpt the particular body part.

- b.

As the limb bud develops, other controls act. The forearm extends, thanks to the actions of two genes that lie in another gene desert. This one’s located near the centromere, which is the constriction in the chromosome. Then, when it’s time to form fingers, the control switches yet again, to another gene desert out on the telomere, the chromosome tip. Other enhancer genes control the formation of the wrist and thumb.

Once again, as I was back in graduate school, I am astonished at the complexity of the cascades of gene expression that guide the choreography that is development. Now I’ll get to that beach read.

I thought that this breaking news might be something you could blog about–

Researchers Shut Down Extra Chromosome In People With Down Syndrome.

The Boston Globe (7/18, Johnson) reports, “Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School have shown that it is possible to do what had once seemed unthinkable – shut down the extra chromosome that causes the developmental problems and intellectual disabilities in people with Down syndrome.” This “surprising” finding, thus “far accomplished only with human cells grown in laboratory dishes – is the fruit of a daring, out-of-the-box approach by a scientist whose work has been shaped by her early experience counseling families of children with disabilities.”

On its website, FOX News (7/17, Grush) reports that the researchers “harnessed the abilities of a naturally occurring gene called XIST that acts as an ‘off switch’ in X chromosomes.” The investigators, “in a culture of stem cells…were able to repurpose the XIST gene so that instead of silencing X chromosomes, it silenced the extra chromosome 21 instead.”

Bloomberg News (7/18, Lopatto) reports that “the most immediate application for the discovery is to learn about how the extra chromosome affects the development of cells, said” researcher Jeanne Lawrence. The research was published in Nature.

The Boston Herald (7/18, Johnson) reports that Anthony Carter, of the National Institutes of Health, which partially funded the research, “Dr. Lawrence has harnessed the power of a natural process to target abnormal gene expression in cells that have an aberrant number of chromosomes.” Carter added, “Her work provides a new tool that could yield novel insights into how genes are silenced on a chromosomal scale, and into the pathological processes associated with chromosome disorders such as Down syndrome.” BBC News (7/18, Briggs) also covers the story.

Yes, it’s a great story, I read the news release a few days ago. But I try to use this blog to introduce topics that the rest of the media miss. The story of the silenced extra chromosome has been around quite a bit already. But thanks for passing it on!

Limb development in tetrapods — animals with forelimbs — is an area of active research in developmental biology. Limb formation begins in the limb field, as mesenchymal cells from the lateral plate mesoderm proliferate to the point that they cause the ectoderm above to bulge out, which is known as the limb bud. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) induces formation of an organizer, called the apical ectodermal ridge (AER), which guides further development and controls cell death. Apoptosis — programmed cell death — is necessary to eliminate webbing between digits.

[…] See on blogs.plos.org […]