When Does a Human Life Begin? 17 Timepoints

I rerun this most-read post about when human life begins every time that the discussion resurges, which is usually in the shadow of proposed restrictions on women’s reproductive rights. Strong feelings always seem to trump biological facts. Confusion among politicians appears to be apparent concerning when certain events begin or structures appear; whether to track development from fertilization (conception) or the last menstrual period; and even the distinction between an embryo and a fetus. A 4 or 6 week prenatal human is not a fetus — the difference is not arbitrary, it has biological meaning.

From October 3, 2013

I’m the author of several college-level textbooks, on human genetics, human anatomy and physiology, and intro biology. I’ve been in this business for decades.

I’m the author of several college-level textbooks, on human genetics, human anatomy and physiology, and intro biology. I’ve been in this business for decades.

Life science textbooks from traditional publishers don’t explicitly state when life begins, because that is a question not only of biology, but of philosophy, politics, psychology, religion, technology, and emotions. Rather, textbooks list the characteristics of life, leaving interpretation to the reader. But I can see where the disingenuous idea comes from that textbooks define life as beginning at conception — it requires a leap off the page. Consider a report from the Association of Pro-life Physicians. After a 5-point list of life’s characteristics from “a scientific textbook,” this group’s analysis concludes with “According to this elementary definition of life, life begins at fertilization, when a sperm unites with an oocyte.”

Being a biologist, a textbook author, and a mother, I’ve thought a great deal about the question of when a human life begins. So here are my selections of times at which a biologist might argue a human organism is alive. I’ll save my opinion for the end.

1. Life is a continuum. Gametes (sperm and oocyte) link generations.

2. The germline. As oocytes and sperm form, their imprints – epigenetic changes from the parents’ genomes – are lifted.

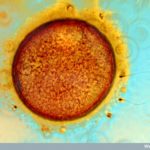

3. The fertilized ovum. Of the hundreds of sperm surviving the swim upstream to the oocyte, one jettisons its tail and nuzzles inside the much larger cell, which becomes an ovum, completing its own meiosis. A fertilized ovum = conception.

4. Pronuclei merge, within 12 hours. After fertilization, the packets of DNA from male and female — the pronuclei — approach, merge, and the intermingling chromosomes pair and part, as the first mitotic division looms. A new human genome forms. Following that first division, some genes from the new genome are accessed to make proteins, but maternal transcripts still dominate development.

5. Cleavage. Divisions ensue. The cells of an 8-celled embryo (day 3) have not yet committed to becoming part of the embryo “proper” (one with layers) or the supportive membranes. Such a cell can still, on its own, develop. An 8-celled embryo whose cells are teased apart could lead to an octamom situation.

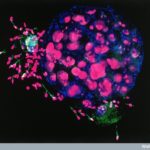

6. Day 5. The new genome takes over as maternal transcripts are depleted. The inner cell mass (icm) separates from the hollow ball of cells and takes up residence on the interior surface. It will become the embryo proper, distinguishing itself from the remaining part of the ball fated to become the extra-embryonic membranes. The icm is what all the fuss about human embryonic stem (hES) cells is about — the stem cells aren’t the icm cells, but are cultured from them.

7. End of the first week. The embryo implants in the uterine lining.

8. Day 16. The gastrula. Tissue layers form, first the ectoderm and endoderm, then the sandwich filling, the mesoderm. Each layer gives rise to specific body parts.

9. Day 14. The primitive streak forms, classically the first sign of a nervous system and when some nations set the deadline for no longer using human embryos in experiments.

10. Day 18. The heart beats.

11. Day 28. The notochord closes, and within it the neural tube forms, preliminary to the spinal cord, while the bulge at the top will come to house the brain. If the tube doesn’t close completely, a neural tube defect (anencephaly, spina bifida, and a few others) results.

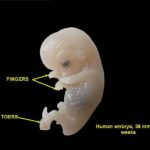

12. End of week 8. The embryo becomes a fetus, all structures present in rudimentary form. Attention anti-choice advocates: before this the prenatal human is not a fetus.

13. Week 14 or thereabouts. “Quickening,” the flutter a woman feels in her abdomen that will progress to squirms and kicks from within.

14. Week 21. A fetus has a (very slim) chance of becoming a premature baby if delivered.

15. Birth.

16. Puberty. The Darwinian definition of what matters on a population and species level, when reproduction becomes possible.

17. Acceptance into medical school. I don’t know where this came from, a joke about Jewish mothers, but in some circles it might now apply to acceptance into preschool. Or when one’s grown offspring leave home.

My answer? #14. The ability to survive outside the body of another sets a practical, technological limit on defining when a sustainable human life begins. That limit may of course change.

Having a functional genome, tissue layers, a notochord, a beating heart … none of these matter if the organism cannot survive where humans survive. Technology has taken us to the ends of the prenatal spectrum, yet not provided too much for the middle, other than fetal surgeries for a handful of conditions. We can collect and select gametes, now thanks to patent no. 8543339. We collect and select very early embryos in pre-implantation genetic diagnosis, allowing those without a specific disease to continue development. And although the gestational age at which a premature infant can survive has crept younger, it hasn’t by much, not since I starting thinking about these things back when I was a stage #16.

Having a functional genome, tissue layers, a notochord, a beating heart … none of these matter if the organism cannot survive where humans survive. Technology has taken us to the ends of the prenatal spectrum, yet not provided too much for the middle, other than fetal surgeries for a handful of conditions. We can collect and select gametes, now thanks to patent no. 8543339. We collect and select very early embryos in pre-implantation genetic diagnosis, allowing those without a specific disease to continue development. And although the gestational age at which a premature infant can survive has crept younger, it hasn’t by much, not since I starting thinking about these things back when I was a stage #16.

Until an artificial uterus becomes a reality, technology defines, for me, when a human life begins.

Live that needs mechanical sustaining isn’t viable life, so i disagree. Life according to your definition is when the infant is capable to sustain itself naturally. So #14.5, premature birth by some weeks.

An embryo, fetus, nor an infant can ever sustain itself independently or just naturally. All of those stages depend on sources other than themselves for growth, health, and life.

:hye there

i was just wondering, is it really true that the heart starts to beat at day 18? wow. it is really early and when coming to think about it i am very surprised and also excited on how it functions so fast “

I’ve spent a great deal of time thinking about this question too. The problem with defining life at the point it can survive is that ‘survive’ is a fairly arbitrary term. A newborn requires a pretty dramatic support system and arguably more intentional care than when it was still in the womb. For this reason I tend to settle at conception which, to my understanding would represent the first truly committed step towards growing a complete human. So, if nothing goes wrong, after conception a human follows. Without conception, no human. Egg on its own, sperm on its own, not going to make a human… but put them together and that is when the magic happens.

I still vote for #1. The question is biologically irrelevant. There is no point in the reproductive cycle at which life begins, all the gametes are alive, the products of their fusion are biologocally alive. There is no point at which any cell involved is not a loving thing.

The question you’re actually asking is when does personhood begin as we don’t actially care about the ethics of ending life, or we would do things like eating (even vegetarian), or exfoliating. So why not ask the real question? When do we care about a nascent human life as a person? That is not biology question even if it may be informed by biological knowledge. My favorite answer is my father’s – when the kids move out and the dog dies.

Thanks Mark. The question about when a life begins is open to opinion, which is why I would not assert when that is in my textbooks. It is biologically relevant to me.

Mechanical sustaining maintains life. I have a friend with a spinal cord injury on a ventilator and he is as bright and alert as anyone, more so than many. Lots of blurry lines with these questions. Thanks for participating.

you’re confusing adults with people to be. A child that get’s delivered and can’t sustain it’s own life isn’t life. It’s a life that destined to not be. That’s how nature meant it, that’s how the genepool stays clean from defective genes. Rejection of the fetus.

Eugenics is being practised on daily basis each time a down/spina bifida/microchepaly etc fetuses are aborted for that reason.

(voluntary) Postnatal abortion of a person with a spinal cord injury is possible in the more enlightened countries where euthanasia is legal.

Discussions are underway to redefine life in extremely demented persons so that euthanasia is permissible as well without consent.

Society moves on, clinging to outdated concepts is called stagnation.

If an unborn baby wasn’t alive it wouldn’t grow or kick inside the womb.

Good points

Incredible post.

I agree: what define a life it’s much more a technological matter then a biological one. The same way technology has changed what ‘naturally’ occurs to humans (from vaccination to in vitro fertilization) the same apply for embryogenesis.

A new line will be drawn in few years from now.

“When does a human life begin?” and “When does an independently sustainable human life begin?” are two very different questions. To the first one, I answer #3. At the moment of conception, we get a new being with all his/her unique genetic and epigenetic information. It’s not just that that life is unquestionably human, that that being is a member of the species Homo sapiens. It’s that his/her genetic and epigenetic information are so personal, and it’s precisely this information which is running his/her development from the begining.

When we introduce the concept of independently sustainable human life, we are walking on a totally different ground. How independent is really the life of a baby, even a toddler?

Thank you, Ricky, for rising this question (and for all your wonderful posts).

Thanks. But epigenetic influences happen throughout life, as environmental influences, both from in the body and outside, alter the methyls, phosphates, and acetyl groups on the chromosomes, controlling which genes are expressed and which are silenced.

Thanks for reading the blog. I’m Ricki, an XX.

What is your definition of life? So the begining of life depends on the definition given.

Gabriel, that question is why I wrote the blog. I can’t answer it, because the answer depends on what hat I am wearing. As a mother of three grown daughters, I’d say what I did in the blog — at the earliest week of viability out of the uterus, which I think is week 22. I’d want my daughters and myself to have the choice to end a pregnancy. BUT … when I learned that the embryo’s genome turns on at day 5, well the geneticist me had to stop and think. I do think that anyone talking about this should be aware of the various stages. When I taught biology in the flesh (not online, in a room with real live people), and got to prenatal development, I brought a collection of preserved human embryos and fetuses to class with me. My kids were little then and came with me and still remember them — one made my middle daughter cry. An obstetrician had donated them in the 1950s. And wouldn’t you know it, the student newspaper wrote it up as me being pro-life (a term I hate), which was not at all what I’d intended. The students were riveted. By sheer accident, I still have one of the embryos, it had fallen into a box of exams. Although I will always be pro-choice, the embryo is in a very special place and I do wonder who it would have become. (The specimens were all miscarriages.) So I guess I can’t answer the question because I compartmentalize it.

Yep, I’m aware you are a XX, my misspelling of your name notwithstanding. Sorry about that.

Thank you Ricki for your well crafted post on the subject of when does life begin.

It certainly is an important question and one which many are debating given the developments we read about almost daily now with regard to Pluripotent cells and their medicinal potential.

Being able to mature into a fully functional entity I would suppose is everyone’s definition of a viable life form. By definition today that therefore requires a Totipotent cell – i.e. one which has the elements needed to develop into a whole organism.

As Pluripotency is a state of a cell beyond the Totipotent stage, that therefore to me represents the line in the sand for the individual cells of the Embryo on a biological viability level…

The definition that Life is apparent in all living tissue is true I suppose if you wish to view it that way. However, to me, there is a big difference between a cell that can create a whole life form and one which is merely a biological machine in a state of action there to serve the whole…

If life is anything it is defined by its ability to survive. So taking this one step further, if a cell is taken from a living Embryo, a Totipotent cell, it can create life under the correct circumstances. However, taking one Pluripotent cell from an Embryo beyond the Totipotent stage, prior to the ICM formation, will result in a Pluripotent cell independent of the continuing viable Embryo. An Embryo that can continue on its own development and produces life, if it’s implanted and passes nature’s own safety tests. This ability to survive is a sign of basic intelligent life IMO but is wholly dependent on nature’s success ratio to become a living being.

In-Vitro Fertilization does just that to an Embryo for diagnostic testing and children are born – however, with the assistance of technology.

On the other hand that Pluripotent cell which was taken out of the Embryo is incapable of developing into an human and has no further purpose biologically other than to help determine viability in the IVF process of the remaining Embryo. Except, and importantly, in Science that one cell can help many millions of people by being turned into other cells of the body – all alive cells but none able to be a human…

Non-Destructive Embryo Intervention is enabling IVF babies to be born to parents that couldn’t create Life and for Medical Breakthroughs to be achieved. Enabling selection while preserving the opportunity for Life and assisting those that are already Alive…

It is by no means a given that the mere viability of an Embryo to become a whole organism will actually become such in the natural order – given the very poor hit and miss ratio of nature’s own reproductive system. Therefore surely the success of nature’s process is a factor in determining when does Life actually begin…

Perhaps when an Embryo passes Mother Nature’s own Life definition and accepts the Embryo into her womb and nurtures it to a reasonably advanced stage without aborting it can we say it’s a Real Baby not just a viable Embryo hoping to be one…

Cheers

Peace at last?

The relevant question here is when is the fetus a person with rights, not when is it alive. “When is it alive?” has got to be the silliest question (although I am sure it is a surefire way to draw attention on the web). It never “comes” alive from an unlive state. This is Biology 101, and Philosophy 101, for that mater.

All life has needs to be sustainable. A blasocyst, a fetus, and a baby all must be taken care of or they die. The difference is the first two use someone the mother’s body to sustain themselves. A newborn has no mental understanding of the world, neither does a blastocyst. There is no difference in their capability to survive on their own. The fetus is a member of homo sapiens. Killing it is homicide. Sometime it is justified, but it is homocide.

Try sustaining a baby without a supermarket and all the technology behind it. You’ll find it quite hard hunting and gathering enough food and clean water for the nursing mother without technology.

By your definition, most humans are not viable life. Not that I like a lot of the other definitions, but this proposal is silly.

I think the author’s definition of “survive” is actually pretty definite and not arbitrary as you say. The author is defining survive as being able to live without a permanent biological connection to another living being. This first occurs around #14 according to the author.

The only reason I disagree with the conception argument is that it is only one cell at that point. It seems odd to define one cell as a human being. If you think about it, one of your skin cells has all the genes and DNA that you had when you were conceived, its just a matter of which ones are activated. I don’t know, its just how I consider it, but everyone is entitled to his or her own opinion.

I agree with Mark. The question should be “When does personhood begin?”. Infants and toddlers probably cannot survive without just about the same amount of support that an embryo or a fetus require. Those under 18 (in this country at least) have both restricted rights and restricted responsibilities. Now “children” are allowed to be dependent upon their parents for health insurance until age 26!! While life itself clearly begins at conception, that is not nearly as relevant a question as when personhood begins.

I appreciate the post, along with the knowledge and careful thought behind it. Demonstrating the difference of opinion that always marks a discussion of this nature, I must go with #3, a fertilized ovum, or conception. I look at the very same evidence, along with raising four wonderful children with my wife, and it seems clear to me that a separate human is coded when the egg is fertilized. The developmental path of a distinct human being is established and, if allowed to proceed naturally, will culminate in a distinct, individual adult. An act of intervention to willfully end this process is undeniably a disregard of any rights associated with that developing human. I look around our country today and I see attitudes prevailing that, in my view, are surely associated with several decades of devaluing such rights. I allow the fact that I could be wrong in my view, but it seems undeniable to me, both the definition of when life begins and the consequence of disregard.

I think it really depends on what you mean by the underlying question. If I ask “when does life begin” I can mean biologically, philosophically or a variety of other things.

Biologically, its more a technical question, and I’m inclined to take the continuum view, after all, the gametes are both alive, so is the cell their combined genetic material forms, so life never really “starts”.

Philosophically you’re referring to personhood more than actual life, at which point I would (of personal opinion) say the primitive streak.

Politically you mean when do we confer rights to the organism, at which point I would say limited rights at week 14.

So really, what we need to know when answering the question of “when does life begin” is what exactly the person is asking. Do they mean it in biological, philosophical, or other terms.

Technically, we humans need mechanical and technological sustenance to live. We have evolved so far away from a natural state that if you threw us out on the Sahara, and forbid us from using tools or technology of any kind, we wouldn’t last long…

If anything I would say mechanical sustenance is one of the prerequisites for human life.

Thanks so much msemporda for a terrific post. For the non-biologists out there, a totipotent cell — that is, a fertilized ovum — can divide to give rise to all the cells of the body, but also the extra-embryonic membranes required for development. The earliest pluripotent cells can’t give rise to the membranes. (Please someone correct me if I’m wrong.) After pluripotent cells, multipotent cells are even more restricted in the daughter cells they can ultimately give rise to. I use “give rise to” because I dislike the media representation of stem cells as “becoming any cell type,” because if they just became everything without the all-important characteristic of self-renewal, they wouldn’t be stem cells.

Sure. Great paper. Published just in time for me to assign it right after my students analyzed 23andMe. Thanks!

Thanks Tesla. That’s why I wrote the blog post. I think I could argue for any of the 17, except perhaps the acceptance into medical school one. I’m a would-be doctor, felled by organic chemistry. I actually like the continuum idea.

This is most interesting Ricki. Folks seem to take the position that fits best with their own exposure to Life. Some even address Spiritual Life and Biological Life both when they discuss the human person. I personally take the position that life is a continuum which can cover both Spiritual Life and Biological Life. I use the Biological definition of life per the classroom and demonstrate that only living parents and living sperm and egg transfer life to a living child. I think the question you are actually addressing is when does a human person begin? The definition of Person as per our Constitution, Law and practice of medicine is where you are headed. The human person begins at conception for moral and legal purposes. Thus DNA is the “finger print” of the physical human.

We need to encourage our students to continue questioning and investigating while respecting and protecting both life and persons.

Hi Mark. Thanks for your post. You can’t be wrong in your view — it is your view. And I agree that being a parent definitely affects how you feel about this.

I don’t think it is silly to study, understand, and wonder about the biology of our beginnings.

First of all, I hardly need to draw attention to myself on the web. I’ve been writing about biology for 30+ years. Second of all, wondering at the biology of human development is not a “silly” question. Inquiry is not silly. Writing an intro biology textbook is neither simple nor trivial. My goal was to start a conversation. That has happened. Glad you could join in.

What a wonderful person YOU are. Hitler couldn’t have said it any better.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, David. I was thinking strictly biologically — personhood is indeed a far more difficult question.

I am Jewish. That is a highly offensive comment. Please do not confuse geneticists with Nazis.

Indeed, parenting has a profound effect on one’s view of this topic. The whole process of human development, at every stage, is an amazing miracle. An up-close view is humbling. I would disagree with your definition, but I am in strong agreement that it would be a vast improvement over what we have today, and have allowed to proceed since 1973. Around that 20-22 week mark might prove to be a sensible social/political compromise in terms of conferring rights to a developing child. I would draw the line at conception, and many would draw no line at all. In any case, your suggestion is a reasoned and significantly better approach than what has been practiced.

I don’t think your article’s list is silly; in fact I thought it was pretty reasonable. I meant to say that defining life as petrossa did, as what can be supported by some modern technology that you like and not by some modern technology that you don’t like, is silly. We’d all have different definitions dependent on how hippy we were.

What I felt was missing from the article was the possibility that this might be a matter of degree, and that it might be meaningful to say an unfertilized egg is alive, but a post-birth baby is more alive in a much more important sense. If you go looking for a black and white boundary, maybe you will find there isn’t really one there.

The comment formatting may not have made it obvious that my post was in-reply-to petrossa at 5:20 pm. I apologize if it was misunderstood.

“Siamese” twins, anyone? This entire discussion is made possible by the anti-life fanatics out there who have been trying to hijack procreativity for use by the power elite. Conception begins a life. For a parallel, look at a zoo’s excitement when a female from some rare species becomes pregnant. Not a life? Not on your life!

While included are the popular and compelling time points such as viability, it doesn’t address the obvious. We consider the end of human life to be the cessation of brain activity, so, why isn’t the beginning of human life considered to be the beginning of brain activity?

Thank you for the comment, but name calling isn’t necessary.

I’ll have to add #18! Thank you. But maybe that goes under the neural tube one.

The key issue about 22 weeks is that it is the point where the person can survive without the mother–if the mother does not want to be the mother, for whatever reason. So from 22 weeks on, instead of an abortion, the mother has a responsibility to, instead have an induced delivery.

Or perhaps the father can act.

Technology as a guide? No. It keeps changing from year to year, until that artificial uterus you mentioned will become a reality. It is inevitable.

What’s missing here is revealed in the previous paragraph, where you list all the possible venues by which to answer this question:

“Life science textbooks from traditional publishers (I’m with McGraw-Hill) don’t explicitly state when life begins, because that is a question not only of biology, but of philosophy, politics, psychology, religion, technology, and emotions. Rather, textbooks list the characteristics of life, leaving interpretation to the reader.”

The key word is “interpretation”. Who interprets? A scientist? A politician? A priest? A student?

And therein lies the flaw. We will never be able to agree on when life begins because it is the wrong question — not one of science, or religion, or philosophy, but of justice. It is not when life begins but when the right to life begins that matters. Our courts have not decided on this because for years we’ve been asking the wrong question.

All of these institutions bring unique and worthy perspectives to the debate. But they should never be used to answer a question that lies at the very heart of our individual rights. They are the servants of justice, not its masters.

The God of the Jewish people had an answer to the question:

“Before I formed you in the womb I knew you…”

Jeremiah 1:5

Since there is no “definitive” moment when life begins, I prefer to give a baby the benefit of the doubt.

Actually, Doctor, you answered the question yourself in your very first point. To whit: “1. Life is a continuum. Gametes (sperm and oocyte) link generations.”

Being that life IS in fact a continuum, consider this: Absent any outside intervention (like abortion) or inside intervention (passing of an unviable fetus to due genetic instability), would that continuum naturally evolve into a complete, viable child able to survive outside the womb?

If the answer is ‘yes,’ then life begins at point number one, i.e., what we commonly refer to as ‘conception.’

When does a single life begin? At conception there is the potential for more than one life. That’s why we have identical twins and triplets. Also, there are the rare cases of human chimeras, individuals formed from the fusing of two separate embryos. All this surely complicates the discussion on the concept of a soul and when it exists.

That was not name calling, simply defining the context.

So just checking to make sure. Rich Americans become “living humans” at 22 weeks (21 being the record holder) as they have access to neonatal wards and the best medicine money can buy. Poor Africans, in contrast aren’t “living humans” until later because they don’t have access to neonatal units.

Of course, as the author surely knows but doesn’t say is the fact that preterm girls are typically viable sooner than preterm boys. If memory serves, for a given amount of support and birth weight, black babies are viable shortly before Caucasion babies. Which of course leads us to yet another fun wrinkle in viability – heavier babies are viable sooner.

As the author knows, 22 weeks is a completely arbitrary number. Some preemies have no chance at all around 22 weeks (low weight, slow development). If we are basing this definition off strict calculation of viability, then we will have differences in the beginning of life driven by socio-economic class, genetics, and maternal location (inside a hospital – it’s alive, 30 minutes from the nearest neonatal unit – it’s not alive).

There is no empirical point of viability; viability is a probability distribution that can be changed by advances in technology. Where the early tail of the distribution allows for a non-zero chance of survival is unknown and unknowable and hence completely unscientific.

NOT BRAINDEAD REQUIRES BRAIN. The features of the human brain required for cognisance and consciousness don’t form until after the 27th week (6 months). Living human tissue is not a person. People’s hair and nails grow after they are embalmed and buried because the tissue is still alive. Beating hearts are ripped out of bodies for transplant. This is why heartbeat and single cell personhood laws are ridiculous.

The egg and the spermatozoon are dying cells. They will die in 24-48 hours if they do not join forces, and what forces! The embryo is alive, and the parent cells would be dead if they had not formed an embryo. It reminds me of the saying that if 2+2 are 4, were to have behavioral consequences, we would never accept that as given, at least there would be people disputing it.

Just trying to get a conversation going. Thank you. Your comments go beyond my intent.

No child can sustain itself. It must be fed, kept warm, etc. By your logic there is no life.

Bravo, I agree.

The thing I can agree with is the beginning of life is a matter of opinion. The author believes that human life should be considered as beginning when the fetus can live outside the human body at about 22 weeks.

Yet, as we speak, NASA is searching for signs of life on Mars by looking for a single cell bacterium. We consider the bacteria that inhabit the human body to be life forms, yet most of these cannot exist outside the body for any length of time.

And there is still ongoing discussion about whether some viruses should be considered life forms, which could be true since many can “live” on a surface, such as a doorknob for hours.

Should we be reconsidering what else we consider to be life?

At 22 weeks can the “life” sense or perceive pain? Shouldn’t we as humans consider this in our discussion?

It is not about financial viability it is about potential viability.

Following your logic this week, one could justifiably terminate their pregnancy just prior to step 14 and no injustice has been committed with regards to genetic defects, quality of life, social economic status, pro-choice, etc. Now, using the argument of: #14. The ability to survive outside the body of another sets a practical limit on defining when a sustainable human life begins.”…Next week the mechanical uterus (Or the technology exists to assist a premature fetus) works and human life is now sustainable outside the body. Did we as a society just aid in terminating life at an astronomical level? Also, did we infringe upon the rights or “choice” of the unborn? So, last week one decides to be pro-choice ( I know you don’t like the term, but we commoners are stuck with it and understand it) and end a pregnancy. This week, taking the new technology into account,we just committed something less than optimal.

I’m just trying to stress the point that we need to set a definite “Red line” on when life begins. Using multiple interpretations can have disastrous effects on our species.

I’ve always enjoyed the analogy my brother experienced his first day in philosophy: “The professor enters the class and says everybody line up from tallest to shortest. The tallest groups will receive high marks and the shortest will fail. To the students disgust, he then stated this was his own interpretation of justice and truth. Fortunately, society does not operate on every-ones “interpretation” of truth, there are clear and defined lines for many things. I would argue that Life, and when it starts, needs to move out of the gray .

Technology will eventually catch up, and when it does, ignorance will not clear us from our indiscretions.

I thought it was pretty clear to all that life, human or otherwise is defined as any cell or organism with an unique set of characteristics capable of developing, growing and maturing to the point it is capable of reproducing itself through mating. Whether this cell and it’s continuing development is dependent on external factors (a womb to grow and feed from, nesting, etc) is a different question. I dont think anyone questions that unicellular, bacteria, or the cell resulting from the mating of a female dog and a male dog is life. So why would a different standard be applied to human new cells?

I’m not sure that I understand criterion #14. Is the point that the fetus is able to survive on its own without receiving extra assistance?

If this is the intent, then many absurdities arise. Persons on life-support, for example, are unable to survive without assistance. Does going on life-support suddenly make one not alive? How much assistance is too much assistance? Is a pacemaker enough assistance to make one not alive? An insulin pump? Does more assistance make us less alive? We all agree that this is not so, right?

Surely the point of life support is to keep one alive until such time as one can get off of life support. Hence the name.

Likewise, the biological function of gestation is to keep the fetus alive until such time as it can function on its own.

So “assistance” is not the criterion, either as a binary category or as a gradated category.

What about “being inside the mother’s body?” Perhaps that indicates that the fetus is actually a part of the mother, not a distinct organism.

But biologists recognize many instances where one organism exists inside another – yet this does not make the inside organism a “part of the other” or “not alive” or “not an organism.” Physical location doesn’t make life into non-life or vice-versa.

I can’t see a way clear to accepting #14 without devolving into absurdity.

Maybe this will help. http://www.unc.edu/news/archives/jun99/wilcox2.htm

There is an exhibit in Portland Oregon with embryos in different stages of development. I have sat and pondered how intricate we each are, how profound….it does inspire and provoke aw and wonder in me. I have three daughters and this discussion is active in our home. Pro-choice, pro-life, adoption….I struggled with infertility, ectopic pregnancy, bed rest etc. I have had the privelage of giving birth to two gorgeous girls and we adopted our middle daughter. Our discussion at home is simple really. As a woman if you are pregnant you have three options. Carry to term and parent, place for adoption or abortion. All three choices are difficult to make and we must respect the women around us. I have many friends that have had abortions that struggle today with their decision. They can not speak of their struggle openly. Our birth mom had to struggle with her decision to relinquish her child by birth to us. And parenting is not to be taken lightly. Thank you for the blog. I will read it with my family.

What an amazing article and comments. Not being a biologist or having any scientific background this has provided me with some specific answers. I have viewed the beginning of personhood as being at conception. My view is that when the unique DNA is formed that defines the new person. If I am understanding the presentation correctly that new DNA is actually happening at day 5.

There are those among our population who are totally dependent on some form of technology for sustaining their lives. I see no difference between the 5-day pre-born child needing the mother to sustain life or someone needing some form of technology to maintain their adult life.

We are using the unique DNA in legal situations to identify people as guilty or innocent of crimes. I believe that unique DNA should define when a human life begins. I can kill some part of me, of my DNA, such as pulling a tooth or removing an inflamed appendix, but I cannot willingly kill something with a unique human DNA. At 5-days that is no longer me, but someone else with personhood qualities. To me it seems simple, but as I said, I am not a scientist.

Thanks for the interesting information.

Although I disagree with you and hold to life begins at conception, I applaud your willingness to draw a line in the sand regarding ‘when life begins’. Too many pro-abortion apologists, sympathizers , activists, etc., will not say ‘when life begins’ wrapping themselves in an arbitrary/nebulous “it’s a personal choice” for each woman. How can life begin at conception for woman A, week 22 for woman B, and 6 months for woman C…. If A, B, or C is right then the other 2 are WRONG. There is no grey area here only touchy-feely “everybody gets a trophy” mushy thinking. Life does begin. If you are a pro abortion rights person, struggle with it, but have the guts to take a stand for when life begins because there are not 2 answers, and everybody can’t be right as to when life begins.

Yes, you got me into your conversation. Looking forward to your posts on time travel and panspermia. 🙂

Seriously, the personhood question is the relevant one. I think it’s clear scientifically that there’s no consciousness to suffer prior to quickening.

I appreciate this discussion very much. Conveniently, for me at least, my personal understanding of “life” leaves this line of questioning and discussion unnecessary. To me the “observer” enigma of quantum mechanics, and the complete lack of evidence that the brain “creates” consciousness (which I believe is the “life” we are referring to) leads me to conclude that the simplest explanation is that consciousness comes BEFORE biology, not the other way around.

There are increasingly complex forms of life, as there are increasingly complex forms of consciousness, and a more complex human consciousness necessitates the more complex life form found in humans.

So when does “life” begin? It doesn’t.

Life or consciousness existed before an egg was fertilized, and it exists after the organism dies. There is endless life, and there are endless forms into which life can manifest itself.

If a complex human consciousness requires a complex organism to manifest a complex human potential, then I imagine a complex brain would be required to accommodate that potential. That certainly doesn’t happen until much later in the development of an human than the embryonic stage.

Now for an even more controversial outcome from this “consciousness first, biology later” reasoning; even if consciousness or life was somehow linked to say an embryo, the destruction of that embryo could not result in the destruction of consciousness or life because there is absolutely no evidence that biology causes consciousness. Upon the destruction of an embryo, an individual consciousness or human life, will simply manifest itself in the next available suitable life form.

Obviously, so much of this is conjecture and beyond scientific validation, but given our complete cluelessness surrounding the cause of consciousness, this is to me a paradigm that may facilitate a new way of looking at challenges like the quantum enigma, and the “hard problem” of the origins of consciousness and life.

This is a very intereting debate or question, however you want to put it?

I will have to say many have discussed this and most fail to ask the simple question first, what is life?

It seems through out time this has been consideredand yet I would say the best way to answer is to consider what few have!

When we as functioning human beings make the statement or ask the questions of doctors, something to the effect of, what is wrong with my arm or I just feel bad, or what is wrong with me?, perhaps the question that is most relevent is who is me, my, or I?

If one considers this question, who is my, I would have to say there is a very obvious answer, we are not our body, our body is simply a conveyance of the life within, so when does that begin?, I would say that is a question that we as humans cannot answer for ourselves, nor can we answer this as far as the relevence of other life and its significance to all other life!

Perhaps it is best stated as it has been said long ago, this is a question which can not be answered, so why try?

Humans are at least to me and my point of view the most arrogent life form that exsists, perhaps we should just take a lesson from a tree or plant, and just be!

Just a thought!

My own feeling is that your #1 is right. Life never “begins,” or strictly speaking only began once (whether you believe in the story of Adam and Eve, or simply that millions of years ago the first bit of protoplasm capable of reproduction came to be). But I would say that your #14 is the beginning of an independent human life: up to that point it is simply a parasitic clump of cells. So I think that up to then it is reasonable to allow abortion, which I imagine you would too, though we define the “beginning of human life” differently. Before that it is only an appendage to the mother’s body, which she should no more be barred from controlling than in an amputation of a limb; after that boint, it is an independent person with a right to life.

I hope you have no problem with my quoting this post, with my own comments, on my own blog.

A couple of thoughts:

First, it seems obvious to me that human life possesses different characteristics and capacities at different points along development. No, a blastocyst does not have brain activity. But, why would we expect it to, anymore than we would expect a four year old to possess the maturity of brain function to drive a car? What a blastocyst does possess are the characteristics and capacities of human life consistent with that stage of human development. And that can be said for every human life, regardless of age or stage of development. Given that, it seems clear that human life begins at either conception or cleavage, because the union of a human ovum and a human sperm is the only point along the line, except for cleavage, that represents the creation of a separate human being, all other points along that line merely representing stages in the development of that human being.

Second, the only reasonable conclusion to this post and the comments that follow seems to be that we do not yet know when human life begins. Given that, the only morally viable position for practical application is to assume that life begins at conception or very shortly after, and to extend to all human beings from the point of conception the dignity and respect accorded to innocent human life. To act otherwise would represent the willingness to destroy innocent human life, and that is certainly homicide in intent, if not in actuality (which can only be proven when we know with certainty that human life does not begin at conception or soon after).

This perspective may be unpopular, confusing or sound exceedingly weird .

Suggestion… read slowly. This will either resonant or not.

A basic misunderstanding generated by a human being’s identification of self as “having a life” vs a human… being life itself… may be a significant perspective that can bring clarity to a mind’s confounding notion about …when life begins.

All answers here are neither correct or incorrect. Sounds like a cop-out…but that is your mind needing to understand a question that has no answer…nor needs one. Science as well as philosophy can be advanced without an answer.

Who is willing to accept that? Not easy. and for those who cannot…

In a democracy, the largest consensus of opinion usually wins out…temporarily… over a span of time. Pick your number above.

Pardon if I’m repeating something that has all ready been stated – Settling on #14 seems to imply a lot of regional and economic variation. In a region where the medical tech required to sustain the life of a baby born premature is not available, “life” thus defined would begin many weeks later. Perhaps (in a place without the medical technology to sustain the life of a full term baby born with a birth defect or accident that requires intervention immediately or soon after birth) life doesn’t begin till some period of time well after some babies are born. In economicly impoverished regions where the infant death rate is very high, perhaps life doesn’t begin for one or two or more years after the date of birth???

Excellent points.

Thank you, you’ve stated exactly my point.

Thanks, you can quote the post. I managed to avoid the “a” word. I appreciate all of these viewpoints. Thanks everyone.

I thought I would try, manofwar, simply because there are so many possible answers. People write a lot about conception, continuum, embryos, premature babies, but I don’t recall seeing a long list of various stopping points along the continuum. I was up to that point in the textbook revision I’m currently working on so thought it would make an interesting post.

Thanks Ej. I started thinking about this a great deal with recent discussion of when an embryo or fetus feels pain. There seemed to be a consensus that a fetus can’t feel pain, but that goes against what I know as a biologist. Neurons work. Synapses are there. Why wouldn’t there be pain? There would be the sensation of pain, but not the perception of it because the fetus would not have experience to provide context. But really we cannot know that until one of us remembers what it was like to be a fetus. So it is unanswerable. But I do know that when I went to my first Bruce Springsteen show when my first daughter was a fetus, she most definitely responded. When the pain issue surfaces, I think about that.

Thanks, Pat. As I said in another comment, the 5 day turning on of the genome stopped me in my tracks too.

I never meant to imply that I consider a non-scientist a commoner. I was only trying to present what I know as a biologist on an interesting topic to many people. I’m a professional writer and am not paid to blog.

Kerri, thanks for bringing this up!

Serious question: Why is it important to determine when life begins?

So, what happens when the largest consensus of opinion in any given democray decides that those people who are sufficiently different from us (ie: Jews, Africans, women, males under the age of two in Bethlehem, or what have you…) do not possess human life and are not persons, and are therefore expendable?

Could it be you think that there are no correct or incorrect answers to this question because you’re confident that you personally will always be on the side of those whose humanity is never questioned?

It probably isn’t. I just wanted to write about the various stages because I’ve rarely seen them all discussed outside of a textbook. Some people might want to know what happens at the various stages.

Well, that certainly relieves those in the wealthy and technologically advanced west of any responsibility to help.

More of us. Less of them.

Please do not judge me or put words in my mouth or say what I do or do not think. I wanted to share what I know about biology to start a discussion. That’s all. That is why it ended with my asking for others’ opinions. Mine is not “right” or “wrong” and I could have chosen several of the others.

It seems to me the real point of contention in this area is not in defining when sustainable life begins, but in defining what criteria society should use to determine when a life is entitled to moral and/or legal rights, including protection from being killed. Talking about when sustainable life begins begs the question, as many people reject sustainability as among the criteria.

Because ideas have consequences, and history demonstrates that those with the power to determine who is and who is not human (which necessarily translates into who is and who is not expendable) are arbitrary in how they wield that power.

Can we be honest and say that that, after all, is what we’re talking about? Who is expendable and who is not?

I haven’t judged you or put words in your mouth. Have I judged your opinion. Yes. Are you of the opinion that all opinions are equal?

What I think this discussion is missing, and my own contribution to it is trying to point out, is that ideas have consequences. We can’t pretend that the idea of when human life begins is nothing more than an academic exercise, as your “That’s all” suggests. Sorry, Dr. Lewis, but that’s not all. History proves otherwise, including contemporary history.

Informative article through the wonderful journey of conception to birth.

I’m not sure that science always offers ethical frameworks for choices. I also believe most minds are made up on this issue upon emotional frameworks – which has its own sets of limits.

Regardless the data enforced my view on the topic.

Thank you.

Your point is that life begins before being “formed..in the womb”?

A neonatologists perspective- biased perhaps but at least based on real life experience:

1. Using your # 14 cutoff. You are right today in a good NICU 22 wks is about the limit of our ability to even mange these kids in a NICU. However, I remeber when it was 24, 26, weeks as well. In addition, the ability of an ObGyn to estimate gestational age ( age from conception ) is never that precise, no matter what technique they use, the 95% confidence interval is +/- 2 weeks. So does this shove the 22 wk cutoff back to 20 weeks. in line with the Texas leislation that was filibustered by Wendy Davis ?

2. For the person saying that pain cannot be felt at 22 weeks. Well my day to day observation is that they do indeed feel pain. Not just reflexic limb withdrawl, but also autonomic responses ( heart rate , blood pressure) but also exhibit facial grimaces in response to, say, an IV being started.

But Ricki is right there is a continuum and discrete boundaries are ultimately arbitrary and driven more by ideology than anything else. My personal vote would be for 8-10 weeks when organogenesis has defined rudimentary organs systems..

By your reasoning a Martian would be correct if they said that I wasn’t alive because if I were placed into a Martian atmosphere I would die. I think the real lesson we are learning here is not when life begins but when does rationalization begin and it begins as soon as someone might be inconvenienced.

Thanks so much for adding your experience.

You would not be alive in a Martian atmosphere. Are you saying being pregnant is an inconvenience? Have you been pregnant?

it is important because of abortion. whether you think that is important, doesn’t matter because others do. I am not a scientist so while this article is really good for me as a lay person, I think future technologies will impact this definition. and as a human being, I think life or even near-potential life is something I don’t want to lose or be part of taking away from others, be it war, capital punishment, unless it can be proven to save lives. Of course, I do kill occasionally weeds, rats and insects, so I am something of a hypocrite. anyway, after this article hopefully some author in the future will comment that on occasion at least, people of this time did try to think and consider serious questions, even though our politics did not reflect that type of effort. Thanks to the author for writing this article.

Thank you for taking the time to comment.

If you define life at the point when it is self supporting then you must define death in the same manner. No more cpr, no additional oxygen, transfusions, organ transplants, no medicines or doctors. Do any of you who are currently living want to go there? I didn’t think so. But, you are willing to impose that on a unique human that cannot speak for himself. HIPOCRITES!

If the things that make us human, the soul and spirit, are present at conception, then destroying the fertilized egg is not much different than putting a gun to the head of a thirty year man and pulling the trigger.

Maybe that is so.

Maybe not.

If not, then its no different than trimming your toenails.

But if it is so, what have you done?

And why have you done it?

Because it’s convenient?

Profitable?

If the thing cannot be firmly established, shouldn’t we err on the side of caution?

This is the source and spring of humanity we’re talking about.

So you’re Jewish– so what? What does that have to do with stating infanticide is monstrous and like what the Nazis did? get over it. I am sick and tired (as everyone else is) of hearing about the Jews and the Nazis. The Romans slaughtered hundreds of thousands of Christians, and I don’t hear Christians today going after the Italians– you God damn jack_ass.

Who is anyone here to say what is and what is not human, when human life does/does not begin? Man can’t even grow a macrocellular chain in a petrie dish, can’t cure the common cold, and I am supposed to think he can define human life? How stupid can you people here be?

I fail to see why anyone thinks the ethics of actions apply to the search for knowledge, or why it matters when human or any life begins. So what if what we learn enables us to do what we ought not to? We already can do what we ought not to! Separate spheres.

Life is indeed a continuum. Death of individual living things is part of the process just as for anything alive, there was a time when that individual creature was not alive. Not news.

Dorothy, you have broken the #1 rule of blogging — we should be civil and respectful to each other and behave as thinking adults. I have requested that the comments be stopped. Thanks everyone for the great discussion.

Yes, 22 weeks is when sustainable life outside the womb begins. “Sustainable” is an adjective that describes a preexisting reality, which is “life”. So, we’re agreed that life must begin before the 22 week point.

The bigger problem, of course, is the adult dependent on a dialysis machine. Given that he’s no longer sustaining life independently without medical intervention, by your definition, loses his right to be called “living”.

I agree, mveal2006, though I would say it is important not only because of abortion, but because of other issues, as well, including infanticide, euthanasia, capital punishment, poverty, genocide, war, etc… I think you alluded to this.

I find you ask two questions. I think your #1 answers the question of when life begins for an individual the best. But the question and answer exist in a context of a historical biological beginning of life yet unknown.

The second question asks when ‘human’ begins. For many people, that is a value judgement rather than a measurable event. Without imposing a value, the best answer will again be #1.

Whatever we determine or decide has consequences in law. And, whenever possible, the law has to be simple. It should avoid gray areas when it can. Above all, it HAS to be based on measurable events; and easily measurable events at that. Imagine bringing all these arguments to bare in an actual trial with a jury full of people who weren’t even smart enough to get out of jury duty. You think all this science will hold sway?

None but the most gruesome among us would advocate legalizing abortion the moment before birth. Call me a pragmatist, but if we want a workable law, that leaves one option: conception. I know it’s hard to argue biologically, and I know 9 months of waddling flatulence is more than a minor inconvenience., but it’s workable. I’m not a big fan of the precautionary principle. It’s overused. But when it comes to matters of life and death, I think it applies.

Life begins at conception. Seems obvious. If this is about abortion, then talk about abortion. I am okay with a woman getting an abortion. Go ahead. But what they want is not think of it as taking a life. They want it to not bother their conscience. Sorry. I am willing to make it legal but I don’t think it is healthy or right to lie to you about what you are doing. We execute people, we go to war and kill people, some women kill their unborn child. I can accept that, why do you need me to lie to you?

The mere fact that we have to as a society to decide when “life” deserves protection under the law shows the deteriation of society as a whole.

We are the caretakers of earth; therefore, should value all forms of life with respect and dignity.

To simply end a “life” because the person has equated it to a nuisance could possibly be determined to being selfish.

To echo another’s sentiments, using technology as basis to determine legality is a frightening slippery slope.

In the US alone, nearly 40 million fetuses have been “aborted”, almost totaling the number of people who died during WW II.

I wonder if the author realizes the greatest number of clincis per capita are within areas stricken with poverty. I also fine it ironic that the greatest number of abortions performed are at places called planned parenthood.

No disease, plague, sickness, cancer, natural disaster, wars, tobacco or any other form of force that ends life can hold a torch to abortion as the greatest vehicle of genocide ever.

I would say “Thank you all for the enlightening and interesting reading,” but I’ll be really tired tomorrow since I couldn’t stop reading, so I’ll just say “Good night.”

Thanks to all those who took my question seriously and answered it seriously.

I accept at face value Dr. Lewis’ answer about wanting to write about the various stages because she’s never seen them all discussed outside of a textbook.

But that response does not answer my real question: Why is the matter of when life begins even asked in the first place?

When I wrote the question I thought the short answer was “politics,” but I think the short answer might be a bit too pat, as “politics” is a loaded word. Maybe “ethics” is a little less so. But then again, isn’t ethics about the behaviors and/ or policies that we think are acceptable and not acceptable, and isn’t that what is about too?

Labels aside, Bob Hunt has two good points. 1) Who has the power to decide who is expendable and who is not?, and 2) what is the criteria for that decision?

Mveal2006 is also right that at bottom it’s about abortion (which is about ethics, and politics, and about Hunt’s points).

The comment that has the most resonance with me is the one that David Gaw made because it encompasses all the others. Further, if we answer his question then we answer all the others too.

The real point of contention is not in defining when life begins, but in defining when moral and/or legal rights ensue.

And no, the debate is not about a woman’s right to choose whether or not to have an abortion. Just as my right to swing my fist ends at the tip of your nose, a woman’s right to choose abortion ends when that right violates the rights of another person.

The primary (only?) practical reason we agonize over when life begins is the presupposition that it is at that point when rights ensue. If not for that presupposition the debate would be nothing more than an interesting academic exercise of little or no consequence.

Is the presupposition correct? (I think not).

Of the many definitions of when life might begin, most of the debate seems to be centered around the point at which the fetus could survive outside the womb. Sharon makes this point quite eloquently, but I’ll add a couple thoughts anyway.

It seems that some argue that it takes extreme measures of care for premature babies to survive, and so even survival outside the womb is not the point at which rights ensue. But aren’t even full term babies incapable of surviving without care? So isn’t the question of viability really a question of relative amounts of care? And eo we really want to go down the path of deciding when life begins and therefore when rights ensue based on some predetermined level of care, which means dollars?

And anyway, isn’t the point at which a fetus can survive much earlier today than it was 10, 20, or 30 years ago? Doesn’t it seem likely that as technology advances that point will continue to be earlier and earlier? Is it all that far-fetched to imagine a time 20, 50, 100 years from now when an egg can be fertilized and grow to full “babyhood” (for lack of a better term) completely outside the womb?

At some point along that timeline into the future, doesn’t the question of when life begins become a matter of some arbitrary, academic, definition, and therefore for all practical purposes moot? How close are we to that point right now? Have we already passed it and we just don’t know it yet?

The real question, the most important question, the question that will never become moot, the question for which the matter of when life begins is really just a proxy, is the one that David Gaw suggested; “When do rights ensue?”

My personal opinion is this: We are all created equal. And while we will probably never EVER really know, outside of some definition that we ourselves rationalize, when life actually begins, we DO know the exact instant at which we are created, and it is in that moment when our rights ensue.

Huh? Petrossa didn’t make such a statement. He clearly stated that it depended upon NOT being dependent on ANY technology. A premature infant which needs an incubator to keep it alive is not a naturally viable infant.

It means (in most cases) that the complex systems that control the womb detected a problem with the fetus and decided to reject it.

Keeping such an infant alive increases the risk of genepool pollution. Statistics show very premature infants die sooner when adult, have more need of medical care during life.

Evolutionary speaking that infant isn’t viable.

The big problem here is the scientific subject gets discussed using emotive arguments. And science & emotions rarely lead to positive results.

Wow. These are the arguments of eugenics (and yes, they were embraced by Hitler .. though that of itself does not make it a bad argument). What does make it a bad argument is your conflation of the terms “life”, “human life” and “independent human life”. A spermazoid is alive. A skin cell is alive. Denying the humanity of a unborn child by declaring it not alive is an absurdity.

“and I do wonder who it would have become” Then we may be asking the wrong question. My question is, at what point does a miscarriage (however induced) result in preventing the existence of a *specific* individual. Those who do not believe fetuses are human do not comprehend why parents mourn over miscarriages. It is because of the loss of particular individual that another pregnancy cannot replace.

Actually it was only after reading Jan Vones comment did the essay make sense to me. The organic mass developing towards an independent existence is so obviously both alive and alive in a uniquely human way that the essay was confusing .. I wasn’t sure of what the question was you were trying to answer. But upon re-reading it and substituting “person with rights” it made complete sense. In other words, the debate should not be over “is this a life, for if it is a life it is murder to end its existence” .. rather the debate should be “at what point does the importance of this life become equal to my own”. (FYI, I fully support abortion rights but I have no delusion that it does not involve the death of an individual. The right to an abortion simply means that the unborn baby does not yet get a say in how the Mother conducts her life).

Yes! Just saw this. My own post was redundant.

She was referring to potential viability. Perhaps it could be clearer is she stated “African in 1921” vs “American in 2013”. The adjective “rich” is just a different way to present the exact same logical case.

When you argue science, you do not have to even discuss the messy thoughts of moral decisions. Our declaration of independence states that all humans have an unalienable right to life, without declaring when that right is in effect. For me, it is conception, because they are on their way to being born human.

Sperm live, but they are not the beginning of the life of a human being. The human being is formed at conception when all the genetic information is joined creating one unique human individual.

Sadly, Ricki has used imprecise language to confound two different questions, and therefore she perpetuates confusion. The sperm, egg, and all their products possess life, and life has been continuous on planet earth for more than a billion years. The question of when a human life begins is therefore misleading.

The true question to be debated is: when should our society grant human rights, and civil rights, to the developing individual?

See how this change of terminology simplifies and clarifies the issue? It also keeps biologists – like me, who make their careers out of the study of life – appropriately distanced from the true debate. Our PhD’s do not give us special leverage on this topic.

Despite genetic alterations later in life, the person was still a unique genetically formed human life at conception. They can alter and transform at genetic levels, but still be the same person. Look at it going backwards. All of us were once a fertilized egg. Before that, none of us was “one” anything, none of us existed physically before conception. Only our components existed.

My goal was to provide biological information because I am a biologist. I left the philosophy and bioethics for others.

Sperm are haploid. A haploid cell cannot develop into an individual diploid individual.

Is a healthy 5 minute old baby truly self “sustaining” outside the womb? Or a 5 week old baby? Or a 5 month old baby? or a 5 year old child? Or a 10 year old? Is an 85 year old “sustainable” on their own in many cases? Should culture allow termination of these by others if for someone else the answer turns out to be “no.” And if so, who should that “other” be? The state? The mother, alone. A child of an elderly parent? Who grants that authority? When does the other come into its authority to terminate? When does that authority transfer to the “child”

The idea of sustainability itself seems arbitrary and leads to a myriad of problems.

Try another approach.

At any step along this process, how ever you define or describe it, the fertilized egg it will develop into an independent self sustaining entity for some period of its existence unless some action is taken to prevent it. Now, of course, many events could derail this process “naturally.” But no one considers an uncontrollable or accidental act to be the willful termination of life. And really what we are talking about is when is it acceptable for one human being to make a willful determination to end a life? The Question is uncomfortable so it is easier to shift the terms of the question to a definition of life and then to endless discussions about the countless descriptors we have for the phases of this process: gamete, embryo, baby, child, adult etc. This seems like a convenient diversion.

The question needs to be focused where it more truly belongs. On the nature of the termination as an act of will. An act of will to terminate only occurs in those cases where allowing the process to unfold will produce a child. No act of will by an other is in play when the termination occurs naturally or accidentally.

At any stage, again barring the accidental or “natural” failure of some kind, the fertilized egg will become a “sustainable” human being unless someone willfully neglects the child, or actively seeks to terminate it. At what ever stage.

If allowed to unfold the process will produce, inevitably and inexorably what we will all agree on is a human being. The only thing that will prevent that is a volitional act of essentially violent interference in this process. This is true at any and all stages of the process. At 6 weeks, at 14 weeks, at 22 weeks, and so on.

The moment doesn’t matter. Every moment along the way is part of a continuum that connects inextricably with the next moment and carries the full potential of the next moment within it. Any act at any time that halts this process prevents a human life from occurring. However you choose to define it.

Again, without that act of will by one human being, another human being will come into existence. Changing this process anywhere along the continuum -requires a determined act of alteration of, or interference in, or violation of the process already underway. “Life” is already underway, in process, moving forward, and will result in what ever entity you choose to finally call “life” So, logically, it is life at every point and its life is already independent since only an act of interference driven by another’s will can change that.

There is a point at which one form of life begins in its form. So the question is when a human being first lives as a human being.

This question of rights being based on dependency intrigues me. To be blunt, an embryo or human is often enough referred as a parasite. Yet there are people in state care, right now, who are legally human, legally alive, who are completely dependent on constant care.

Some would say that yes, but they can be passed on to another person’s care. That is often, but not always the case. I could be closed off from civilization for weeks or even months due to living in a remote location in blizzard conditions, but that does not give me the right to kill my children or abandon them to die.

The way I see it, we cannot possibly control the gestation of a pregnant woman, especially against her will, but we also do not have to, as a civilized society, take part in killing the unborn within her if she does not want to keep the pregnancy. It is at that point, if she so chooses, that we could say civilization breaks down in reference to her, it won’t support her.

A woman in this case is not unique. There are endless everyday cases where civilization breaks and is remended, often entirely depending upon one person doing what only they can do, whether it be for a minute or an hour, or weeks, months or years. Conscripted soldiers defend the country. A bystander calls the police to report criminal activity. Parents feed their children. Adult children feed and tend to their elderly parents. Doctors, worn to exhaustion, remain and tend to emergent care cases. Their loved ones wait and support them. A reluctant leader stands and takes a mantle they don’t desire but which is required for the welfare of the whole.

There are so many times individuals are called upon by society to bear adversity, pain, discomfort, even risking their lives just so civilization can continue. It’s not just about life but human life, and what kind of human life we want to have. Abortion on demand is not civilized.

This is getting polemic. The basic premise is, is the infant born capable of full body control functions as it should at the moment of conception. If it isn’t it would die in nature regardless the care of the mother so it isn’t viable. Non-viable life is life that is not meant to be which equals to no life.

As i said earlier eugenics is a regular daily practice in many civilized parts of the world. In even more civilized parts even postnatal abortion is possible within a timeframe of a couple of hours

[…] recently read this super interesting article on the 17 time points of When Does Life Begin? *From the website PLOS Blogs: perspectives on Science and Medicine. (If you ever want to lose […]

[…] the charge recently from Answers In Genesis’ Ken Ham. Ham responded to an article in which a public-school textbook author wondered about when life begins. Ham’s argument can […]

I am not a “public school textbook author.” My textbooks are for college students.

[…] When Does Life Begin? article […]

Thanks. Ricki, not Ricky. I’m a she.

You identified a number of developmental milestones in the life of an individual. At no point did you explain why any particular milestone conveys “human-ness”. There is only one point, logically, at which the life of the human begins and that is the moment a diploid xygote is formed. Everything after that does not change the fundamental nature of what that thing is.

But that first point is just a cell. It has potential, but not yet what I would call a human being. Assigning a time point is a matter of personal opinion. My point in this post is that many people assign that point without knowing much about biology – or dismissing it.