Disappearing Down Syndrome, Genetic Counseling, and Textbook Coverage

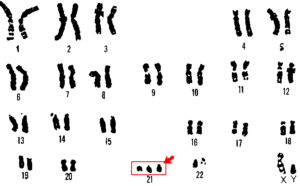

Last week, several people sent me a perspective piece by bioethicist Art Caplan in PLOS Biology, “Chloe’s Law: A Powerful Legislative Movement Challenging a Core Ethical Norm of Genetic Testing.” The concise and compelling article considers legislation to mandate that genetic counselors talk to their patients more about positive aspects of having a child with trisomy 21 Down syndrome.

Last week, several people sent me a perspective piece by bioethicist Art Caplan in PLOS Biology, “Chloe’s Law: A Powerful Legislative Movement Challenging a Core Ethical Norm of Genetic Testing.” The concise and compelling article considers legislation to mandate that genetic counselors talk to their patients more about positive aspects of having a child with trisomy 21 Down syndrome.

WHAT’S THE CONNECTION?

Studies show that as availability of prenatal screening (for risk) and testing (for diagnosis) for the condition have increased, births of affected children have decreased. That is, most pregnant women who learn that the fetus has trisomy 21 Down syndrome end the pregnancy. Yet genetic counseling is, historically, largely value-neutral or “non-directive.” Offer the medical facts, explain how tests work and what results mean, listen, and try to intuit the patient’s views to guide word choices. (“Termination” vs “abortion,” for example). Answer questions, but don’t try to sway clinical decision-making.

At least two hypotheses can explain the declining numbers of newborns with trisomy 21.

#1: Genetic counseling is influencing decisions to end affected pregnancies. That’s the assumption behind the legislation that Dr. Caplan discusses.

#2: Parents-to-be and the general public do have access to a great deal of information about Down syndrome and many of them make informed choices. They are electing not to bring children into the world who would face a high likelihood of having certain medical and cognitive problems.

I concur with Dr. Caplan that mandating genetic counselors to more positively spin life with trisomy 21 Down syndrome may obscure the medical and scientific facts, misleading patients.

PLOS BLOGS suggested that I weigh in on the matter, and I can, from two perspectives that complement Dr. Caplan’s. I’ve been providing genetic counseling since 1984 for a private ob/gyn practice, and I’ve written eleven editions of a human genetics textbook for non-science majors, starting in 1993.

PLOS BLOGS suggested that I weigh in on the matter, and I can, from two perspectives that complement Dr. Caplan’s. I’ve been providing genetic counseling since 1984 for a private ob/gyn practice, and I’ve written eleven editions of a human genetics textbook for non-science majors, starting in 1993.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, I often met with women who were of “advanced maternal age” (35+) explaining the benefits and risks of having the invasive procedures amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS) to check fetal chromosomes. But since the Internet arrived, I do very little counseling of this type because patients can learn much of what I’d tell them on their own. Today patients can know more about genetics than their physicians.

TRISOMY 21 THROUGH 11 EDITIONS

The editions of my textbook chronicle the possible link between the increase in prenatal testing and the shrinking population of people with trisomy 21. Each new edition arises from updating and a wealth of feedback: from instructors and students, from researchers I interview, essays contributed by families, and most importantly, what I’ve learned at professional meetings, where talks can be months ahead of publications.

Like genetic counseling, textbook coverage of trisomy 21 already presents the negatives and positives.

Most of my book’s information about trisomy 21 is under the heading “Abnormal Chromosome Number.” I can’t be politically correct about that – normal means “common type” and an extra chromosome is not common. The section expanded abruptly at edition 4 (2001) as chromosome maps filled in with findings from the first sequenced human genomes. But the introduction remains historically accurate, even if the language is offensive today:

Most of my book’s information about trisomy 21 is under the heading “Abnormal Chromosome Number.” I can’t be politically correct about that – normal means “common type” and an extra chromosome is not common. The section expanded abruptly at edition 4 (2001) as chromosome maps filled in with findings from the first sequenced human genomes. But the introduction remains historically accurate, even if the language is offensive today:

“The characteristic slanted eyes and flat face of the Down syndrome patient prompted Sir John Langdon Hayden Down to coin the inaccurate term ‘mongolism’ when he described the syndrome in the 1880s. As the medical superintendent of a facility for the profoundly mentally retarded, Down noted that about 10% of his patients resembled people of the Mongolian race. The resemblance is coincidental. Characteristic facial features are associated with many inherited disorders. Males and females of all races can have Down syndrome.”

Early editions then described the signs and symptoms, followed with: “These people tend to have warm, loving personalities and enjoy art and music. Intelligence varies greatly, from profound mental retardation, to those who can follow simple directions, read, and use a computer. One young man with Down syndrome graduated from junior college; another starred in a television series.”

In the mid editions I added comments from parents that addressed the subtleties of the condition. “He once dialed 911 when he stubbed his toe, because he’d been told to do just that when he was hurt,” one mother told me. I chose photos that showed young people with Down syndrome doing things – cooking, painting, reading, a little girl banging a toy xylophone. But then I had to respond to reviewers’ criticism that students couldn’t distinguish the “stories” from “what they had to know for the test.” Gradually, the human details that I so love to write about became boxed readings, captions, and tables.

In the mid editions I added comments from parents that addressed the subtleties of the condition. “He once dialed 911 when he stubbed his toe, because he’d been told to do just that when he was hurt,” one mother told me. I chose photos that showed young people with Down syndrome doing things – cooking, painting, reading, a little girl banging a toy xylophone. But then I had to respond to reviewers’ criticism that students couldn’t distinguish the “stories” from “what they had to know for the test.” Gradually, the human details that I so love to write about became boxed readings, captions, and tables.

Responding again to reviewer feedback, I shortened coverage of what parents can do to help their child, instead focusing on the science. Edition one mentioned the value of hanging a colored mobile over a child’s crib. That went. Edition eleven explains how researchers have harnessed X inactivation to shut off the extra chromosome 21 in cells of people with Down syndrome, providing a new way to study the pathogenesis. But I never sacrificed the humanity. Opposite a figure on the new technique a photo shows a young woman intently painting a portrait of a tree. The caption: “Many years ago, people with Down syndrome were institutionalized. Today, thanks to tremendous strides in both medical care and special education, people with the condition can hold jobs and attend college. This young lady enjoys painting.”

I often give patients pages from my textbook, because it offers both sides. The coverage has always included the hard facts that genetic counselors impart: “About half of babies with Down syndrome die before one year of age, often due to malformations of the heart or kidneys. Other patients must undergo heart surgery or suffer often from common illnesses.” Complications also include poor immunity, intestinal blockages, increased leukemia risk, and the high risk of developing Alzheimer disease in later years. But then the balance: “However, some people with Down syndrome are relatively happy, healthy children and young adults. Unfortunately, the test that diagnoses Down syndrome in a fetus cannot detect how severely affected the child will be. The decision of whether to terminate such a pregnancy or raise a child with Down syndrome is very difficult.”

The book is more about the science than counseling, explaining chromosome imbalances and the puzzling maternal age effect. We’ve come far from the 1909 study that blamed “maternal reproductive exhaustion.” And the list of genes implicated in the syndrome has grown as the human genome has given up more of its secrets. Before that, we could only deduce the responsible genes from individuals who had partial third copies of chromosome 21.

The book is more about the science than counseling, explaining chromosome imbalances and the puzzling maternal age effect. We’ve come far from the 1909 study that blamed “maternal reproductive exhaustion.” And the list of genes implicated in the syndrome has grown as the human genome has given up more of its secrets. Before that, we could only deduce the responsible genes from individuals who had partial third copies of chromosome 21.

Bioethics explosively entered the Down syndrome coverage in edition 9 (2010). A boxed reading analyzed a study from Denmark cited in Dr. Caplan’s article. Government researchers there tracked trisomy 21 cases after broadening availability of screening and diagnostic testing. From 2000 to 2006, the number of affected newborns was halved, those diagnosed prenatally increased by nearly a third, and the number of diagnostic tests (CVS and amniocentesis, which are more invasive than maternal blood test screening) fell by half.

The trisomy 21 story really changed in the current edition, with the boxed reading “Will trisomy 21 Down syndrome disappear?” It considers the impact of screening cell-free DNA in the maternal circulation for fetal DNA. Available since 2011, it’s leading to diagnoses in women under 35, while enabling many pregnant women over 35 to avoid invasive tests. The box quotes two New Zealand researchers who published a paper in May 2013 that enraged several groups into demanding the bioethicists’ resignations. To quote from the paper would be out of context. But they say what I suspect at least some genetic counseling patients are thinking when weighing their options and choosing to end pregnancies to avoid the possible medical risks and realities of Down syndrome.

In the 12th edition of my book, I’ll discuss legislation, like Pennsylvania’s Chloe’s Law, that Dr. Caplan so artfully describes. I agree with him that if laws compel genetic counselors to talk more about the happy healthy xylophone-banging little children, and less about the toddlers who sport scars from heart surgeries or develop leukemia, patients might leave counseling sessions with skewed views of life with an extra chromosome 21.

In the 12th edition of my book, I’ll discuss legislation, like Pennsylvania’s Chloe’s Law, that Dr. Caplan so artfully describes. I agree with him that if laws compel genetic counselors to talk more about the happy healthy xylophone-banging little children, and less about the toddlers who sport scars from heart surgeries or develop leukemia, patients might leave counseling sessions with skewed views of life with an extra chromosome 21.

As a single mother to a wonderful but lower-functioning 24-year-old son who has Down Syndrome, I wish our genetic counselor had been able to better give us details about the POSITIVE side of raising a child with Down Syndrome — the “human” side. Even now, years later, all I pretty much recall is him telling us all the NEGATIVE, PHYSICAL part of the equation. It was a devastating experience for me and a horrible pregnancy because of the “gloom” hanging over it the entire time I was pregnant. I literally cried myself to sleep each and every night.

I’m glad that you’re providing a balanced approach to portraying Down Syndrome in the information book you mentioned. The idea that all will be bucolic and there will be few problems, health or mental, for babies, then children, then adult children with Down Syndrome is all too pervasive today.

Thanks for sharing. It sounds like you are a wonderful mother. I have a relative with Down syndrome who is about your son’s age. The mom was quite young and therefore hadn’t had any prenatal testing, and it was a surprise. I remember her calling me. But of course she and her husband fell in love with their boy right away. He had heart surgeries, and I’m sure things were very tough, physically. But the few times I’ve seen him at family events, he is charming and sociable and just fun to be around. He’s turned out okay, but the future is uncertain. Thanks again for writing, and best of luck to you and your son.

It is also a very variable syndrome. Some young adults are in fact more intelligent than others without the syndrome. Some are very healthy; some die from complications of a respiratory infection. And the testing, at least as it is today, can’t predict all of the manifestations. I also think that people/patient’s thoughts about what they would do with a prenatal diagnosis change over time and circumstance. The most important point, I think, is that what to do remain a personal choice. Thanks for writing!

Viewing a child with Down syndrome (or other identifiable genenetic difference) as a reflection of a personal choice, is denying that this child is full fledged person. Parents not wanting a child with Down syndrome will likely not appreciate children who develop cancer, suffer oxygen deprivation, autism, or other ‘extra needs’. Those people should seriously consider to not procreate. Unconditional love and respect for all human beings are human traits that should be cherished. The opposite is happening.

Thanks for sharing.

This post reminds me of an article that talks about genome sequencing for newborn babies. Although gene sequencing is a potential tool in detecting various diseases for children, some parents still don;t want to accept that because of some moral issues.

Yes it is similar. I’m about to start reading a novel about a time and society in which genome sequencing is mandatory. I’ll post about it! Thanks for your comment.

Am I understanding correctly that you think that the term “termination” is ‘value-neutral or “non-directive”’? As a mother to a boy with Down syndrome and, more importantly here, a former ASL Interpreter, I don’t hear neutrality in that term. There is 1 sign for both abortion and termination so the difference would be conveyed by facial grammar and affect. I can’t really imagine that term coming from the professional to the patient without a great weight of importance.

Are you aware of the book “Gifts” which is a collection of essays written by mothers of children with Down syndrome? Perhaps it would help to read that. Mothers by and large report a presumption on the part of the medical professionals that they dealt with a termination was wanted, and it is reflected in that collection.

I didn’t know during my son’s pregnancy (my first), and my doctor approached testing with: if you can’t think of something that would make you choose to terminate there’s not a need to test. I know that with our second pregnancy we were referred for our ultrasound to a more sophisticated clinic. However, the OB-Gyn I’d seen since age 16 had retired and the partner that did the referral didn’t tell me that this place performed therapeutic abortions and that I would be required to consult with a geneticist before the scan. That was all a surprise on the day of. I didn’t have a a heads-up so I did no special research before the visit, but still — as you alluded to — had more up-to-date information than the professional before me. She explained the odds that at my age my second child could also have Down syndrome with research that was 10 years older than what I had found on my own when I first realized I was pregnant. It was off-putting and less that trust-inspiring in the whole clinic. I was able to point out old information and errors on each handout she tried to give us. Not that different from the geneticist that the hospital called in when our son was 3 days old; he gave us an out-of-date book that said things like “average life span of 25 years,” and “low incidence of dental caries” which were from the days when people with Down syndrome were routinely institutionalized. I’m not asking for sugar coating the truth, but this inaccurate information sure didn’t help us at all.

I see that you are doing your best to pass on good info, but in my experience a chat with parents further down the path would provide more insight than a consult with a geneticist. It would be similar to the hearing screenings that newborns receive, where a positive hearing-loss result means that parents are referred to professionals and to advocacy groups so they get not just a medical perspective (here’s everything wrong), but also a perspective on what living with deafness and raising a child with deafness is like. It’s a wonderful model.

Perhaps you could find a local self-advocate/parent support group that can tell you of a parent of a person with Down syndrome who also holds a PhD in the sciences that you could have chat with over coffee? That might provide you with more data and a different perspective on what a neutral perspective sounds like.

Thanks for sharing. I have spoken with parents of an individual with Down syndrome, my cousins. I’ve known their son at all ages, from the surprise at birth (his mom was too young to have been tested) through the surgeries and infections, to today as a charming, healthy, and active 25-year-old. I agree that patients often know more, sometimes much more, than the so-called professionals, and that meeting with a parent can be much more informative than any test results. But I use the word “termination” in discussions with patients because they find it less upsetting than the word “abortion,” which conjures images, for some, of protests with signs displaying body parts and blowing up clinics and killing doctors. My language choice is to make the patient most comfortable. I’m afraid there is no neutral word for such a harrowing decision.

As an Assic Professor of Biochemistry and mother of a child with Down Syndrome, I will have to go look at your text. I can’t judge from these excerpts whether it is really balanced. However, whatever your intentions may be, the message given to patients by medical professionals is unrelentingly negative. Both in my experience and that of many parents I talk to. The information provided to us at several medical centers was out of date, there was an assumption of termination upon prenatal diagnosis, even if the language was “neutral”. I’m not concerned about sugar coating the truth. I am concerned about providing inaccurate information and huge implicit bias even when accurate information is given.

Thanks for writing. I do try to think as a parent/patient when deciding what to include in the textbook, although coverage reflects suggestions from reviewers. The book has a feature called “In Their Own Words” in which family members discuss what day to day life is with a person who has a genetic or chromosomal condition. The one on XXY was particularly eye-opening for me — the man was so accomplished. There’s one on a little girl with GAN, one with Crie du chat — I try to emphasize what people with certain conditions can do in addition to what they cannot.

Hi and thanks for using the photo of my son Jordan (the cheery boy with the cordless screwdriver from Wikipedia).

He is now 28 years old.

Good things: (brag list) he is an accomplished skier, and has skied in the Canadian Rockies, Scotland, the French Alps and New Zealand

He climbs mountains, canoes independently, and has sailed in an old fishing boat around the UK.

He has travelled the world: Egypt, Australia, Finland etc

He uses a mobile phone and computer, and has plenty of life skills.

Not so good things:

He developed Autism and also Diabetes T1 in his early 20’s, and these make life quite difficult for him.

We love him to bits, he is very loving and affectionate, and has learned many independent living skills. But he is a handful, and some of his behaviours are ‘odd’. He will never find a girlfriend or get a job, sadly.

However, his life has as much value as mine or yours, and it is just different. Now worthless or futile, not a burden.