Did Christianity Speed Chicken Evolution?

Did a Christian dietary practice speed the evolution of the domestic chicken about 1100 years ago? A new report in Molecular Biology and Evolution suggests this may be so.

Did a Christian dietary practice speed the evolution of the domestic chicken about 1100 years ago? A new report in Molecular Biology and Evolution suggests this may be so.

The researchers, from the UK and Germany, analyzed variants of two genes using a molecular dating technique that they developed, on ancient chicken bones.

SELECTING CHICKENS

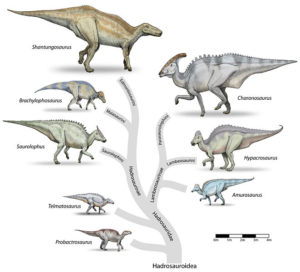

People domesticated Gallus gallus domesticus from wild Asian jungle fowl about 6000 years ago. The chicken genome sequence was published in 2004, but for time tracking, less information is more. Researchers compare DNA sequence variants of corresponding individual genes among pairs of species to build evolutionary tree diagrams, assigning approximate times of divergence using known mutation rates against a timepoint such as fossil evidence from a specific rock layer or an historical event. A branch from the ancestral wild fowl morphed into chickens as humans selected and bred birds displaying traits that made them easier to raise and tastier.

The selected genes encode the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) and β-carotene dioxygenase 2 (BCDO2). Their DNA sequences echo positive selection: mutation changing an amino acid from the ancestral to the derived species. A genetic change that doesn’t alter the amino acid wouldn’t change the phenotype (observable traits), so couldn’t affect evolution.

The two genes confer valuable (to us) traits. Two copies of a variant of TSHR enable many domesticated animal species to reproduce continuously, rather than seasonally. In chickens, the change speeds egg-laying while tempering aggression and fear of people.

A common variant of the other gene, BCD02, cleaves carotene, removing the orange pigment from digested food and rendering the skin white or grey. A mutation new to the domestic chicken, acquired from errant mating with the grey junglefowl (Gallus sonneratii), hampers the carotene-cutting enzyme, providing the familiar yellow color to the skin of a well-fed bird. People probably came to regard yellow skin as a sign of a healthy chicken and selected for it.

The researchers obtained ancient DNA from an archaeological collection of chicken bones going back some 2200 years, from across northern Europe. The bones are abundant from the 9th to the 12th centuries AD. Computations using the degrees of difference among the gene variants in the domesticated chickens compared to their wild relatives led the investigators back to the High Middle Ages, around 920 A.D.

What was happening then?

Christian edicts began to enforce periods that forbid consumption of meat from four-legged beasts, somehow not considering chicken to be meat. The practice spread, with Christianity, across Europe and was ubiquitous by about 1000 AD.

Like a 20-piece KFC bucket today, demand for chickens a millennium ago might have put selective pressure on the genes that enable frequent egg-laying and yellow skin. At about the same time, expansion of cities might have favored stuffing chickens into tight quarters rather than grazing large quadrupeds like cows and pigs.

“Ancient DNA allows us to observe how genes have changed in the past, but the problem has always been to get high enough time resolution to link genetic evolution to potential causes. But with enough data and a novel statistical framework, we now have timings that are precise enough to correlate them with ecological and cultural shifts,” said Liisa Loog, first author, from the Palaeogenomics and Bio-Archaeology Research Network at the University of Oxford.

Chicken evolution continued. Many modern characteristics come from breeding during the Victorian era between native European birds and exotic Asian chickens. Still, the researchers conclude that “to our knowledge, this is the first example of pre-industrial domesticated trait selection in response to a historically attested cultural shift in food preference.” The work also shows that domestication of plants and animals isn’t a quick genetic switch, but a long process, continuing for thousands of years past initial attempts to control breeding, in response to a changing natural environment as well as to the dietary desires of humankind.

Chicken evolution continued. Many modern characteristics come from breeding during the Victorian era between native European birds and exotic Asian chickens. Still, the researchers conclude that “to our knowledge, this is the first example of pre-industrial domesticated trait selection in response to a historically attested cultural shift in food preference.” The work also shows that domestication of plants and animals isn’t a quick genetic switch, but a long process, continuing for thousands of years past initial attempts to control breeding, in response to a changing natural environment as well as to the dietary desires of humankind.

LAYING CLAIM TO CHICKEN SOUP

I have a slight bone to pick with the researchers. From my experience, chicken soup (a surrogate for Gallus gallus domesticus) is more a Jewish staple than a Christian one, and Jewish origins certainly lie closer to the domestication of chickens 6,000 years ago than do Christian origins. Chicken soup is, of course, also known as Jewish penicillin. Archaeology tells us that pottery that could have cradled soup existed in Japan and China some 18,000 years ago, so delivery method wasn’t a problem.

A little closer to the Christian claim, Greek physician Galen, in the second century AD, recommended chicken soup to treat leprosy, migraine, fever, and constipation. In the 12th century Maimonides also recommended chicken soup to treat leprosy, as well as asthma and malnutrition.

Then in the journal Chest in 2000, University of Nebraska pulmonologist Stephen Rennard MD published his landmark “Chicken soup inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis in vitro,” demonstrating an anti-inflammatory effect of his grandmother’s chicken soup. The experiment was actually conducted in 1993 in Dr. Rennard’s kitchen and was quite well-controlled in terms of analyzing ingredients. Here’s the recipe, but I’d leave out the parsnips and turnips (they’re bitter) and the sweet potato is just weird. Up the carrots for a sweet soup.

Then in the journal Chest in 2000, University of Nebraska pulmonologist Stephen Rennard MD published his landmark “Chicken soup inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis in vitro,” demonstrating an anti-inflammatory effect of his grandmother’s chicken soup. The experiment was actually conducted in 1993 in Dr. Rennard’s kitchen and was quite well-controlled in terms of analyzing ingredients. Here’s the recipe, but I’d leave out the parsnips and turnips (they’re bitter) and the sweet potato is just weird. Up the carrots for a sweet soup.

While I’m not an expert in Christianity or math, or even Judaism, I do know how to make Jewish chicken soup. (One of my best friends surreptitiously slips in a cube with a chicken cartoon on it.) It’s easier than Dr. Rennard’s grandma suggested. So here it is:

1. At night, before bedtime, stick a small whole chicken, 2 or 3 handfuls of baby carrots, a small onion, and a stalk of celery, plus salt, pepper, and a bit of cilantro, into a crockpot and fill it with water. Turn the crockpot on low, remembering to check that it is plugged in.

2. Sometime the next day, remove the collapsed chicken, onion, celery, cilantro, and some carrots. Either strain into a pot and pour it back into the crockpot, or fish out the chicken from the crockpot, but this can leave behind bone slivers or gross stuff. (Note: Cats will not eat chicken cooked this long. Don’t even try. Just discard.)

3. About 2 hours before consumption, throw in, uncooked, (a) noodles, (b) rice, (c) matzo balls (aka kneidlach, (d) dumplings (aka kreplach), or (e) any combo of the above.

Because the yellow skin and the fat blobs that cling to it are essential to a good soup, it’s pretty clear to me that the attribution of the invention of chickens or their soup to Christianity is crying fowl.

[…] Did Christianity Speed Chicken Evolution? – PLoS Blogs (blog) […]

[…] Source: Did Christianity Speed Chicken Evolution? […]

[…] Did Christianity Speed Chicken Evolution? by Ricki Lewis. […]

[…] Source:https://blogs.plos.org/dnascience/2017/05/04/did-christianity-speed-chicken-evolution/ […]