Babycat may have been a “naturally occurring model of Alzheimer’s disease,” according to a new report in The European Journal of Neuroscience…

Organoids Model Spinal Cord Injuries

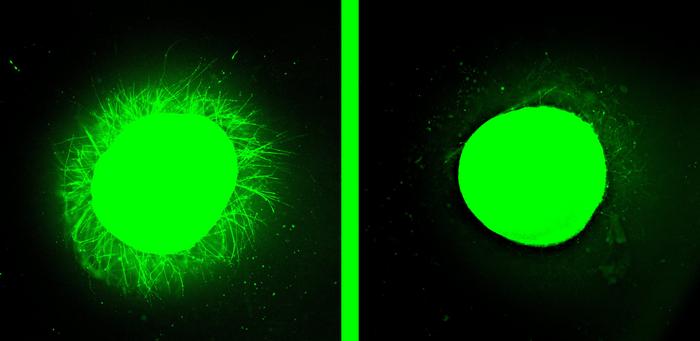

The spinal cord organoid on the left sports tiny nerve cell outgrowths after treatment with peptides that researchers call “dancing molecules.” These tiny bits of human spinal cord serve as models for testing treatments for injuries. (Credit: Samuel I. Stupp/Northwestern University)

The spinal cord organoid on the left sports tiny nerve cell outgrowths after treatment with peptides that researchers call “dancing molecules.” These tiny bits of human spinal cord serve as models for testing treatments for injuries. (Credit: Samuel I. Stupp/Northwestern University)

Organoids are tiny bits of organs nurtured in lab glassware from stem cells. I joke about them at Halloween, when a few drops of water on tiny sponge brain and heart precursors bloom into mini-organs.

A Bridge Between Animal Models and Clinical Testing

Real organoids are a brilliant tool to investigate biological processes and test new treatments. Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells are grown from a patient’s skin fibroblast cells, providing a platform to test individualized interventions. And iPS cells are much closer to the human condition than a fruit fly, worm, zebrafish, rodent, or even a primate model.

Organoids aren’t complete replicas of organs, but mimic how cells assemble into tissues of a specific organ, and how those tissues interact. They offer an increasingly important step between testing a treatment in an animal model and in people in clinical trials, saving time and funding and improving safety and efficacy.

The most recent report of a novel organoid to capture my attention is a mini human spinal cord, which researchers at Northwestern University created to model different types of injuries to test regenerative treatments. Like a spinal cord in a body, these miniature bits of humanity display inflammation, cell death, and the clumping of glial cells into impenetrable scar-like masses that can squelch nerve healing and regeneration.

Cells of the nervous system include neurons and several types of glial cells that provide support and nurturing biochemicals. A neuron’s axon transmits electrochemical information and dendrites receive it. Axons and dendrites are collectively termed neurites.

The human spinal cord organoids are only a few millimeters in diameter. The findings of the new study appear in Nature Biomedical Engineering (alas, behind a paywall), and update work on mice published in 2021 in Science.

“Dancing Molecules”

Biotech advances are easier to understood for folks not schooled in molecular biology if given tantalizing names – like cloning and CRISPR. Spinal cord organoids are sculpted using what the researchers call “dancing molecules.” These are designed and synthesized peptides – strings of amino acids not long enough to be considered proteins. I think the term is a bit condescending, anthropomorphic, and oversimplified, but it’s used often in publicity for the research.

The researchers tested two types of peptides. Each includes a stretch of amino acids that function as a signal sequence, which directs the peptides to particular cell parts. The strategy delivers more than 100,000 peptides, whose movements then activate cell receptors in a way that stimulates natural signals to regenerate and repair the tissue. Introduced as a gel, the material mimics the extracellular matrix, a complex dense network of collagen and elastin nanofibers that takes up a lot of the space between cells in a body. The researchers call their tool a “platform of supramolecular therapeutic peptides,” or STPs. So dancing molecules is a more memorable term after all.

Whatever the peptides are called, they act as scaffolds that physically guide neurons to sprout neurites. One type of peptide reduces glial scarring while the other knits new blood vessels, a logical therapeutic combo.

Groundbreaking Experiments in Mice

The experiments in 2001, on mice with the equivalent of paralyzing human spinal cord injury, revealed that the peptides form fibrils that move. Their rapid oscillation extends axons, reforms the myelin sheath, and entices a blood supply to approach, all of which promote survival of the motor neurons that innervate muscles.

The researchers injured the mouse organoids in two ways – a straight cut to mimic a laceration, and compression, to mimic a contusion that might happen from a fall or car accident if in a person. Neurons died as glial scars grew.

Injured mice given a single injection of the contorting peptides 24 hours after injury were able to walk within four weeks. And when the investigators repeated the experiments with molecules that danced at different rates, the faster ones worked better. As inflammation ebbed and scars retreated, neurites extended as the tissue healed.

On to Human Organoids

The moving fibrils in the human spinal cord organoids echoed the activity in mice – neurons extended as scars diminished, over a few months. Added to the mix were microglia, which are immune system cells in the brain and spinal cord. They quell inflammation.

Stupp describes the achievement. “The glial scar faded significantly to become barely detectable, and we saw neurites growing, resembling the axon regeneration we saw in animals. This is validation that our therapy has a good chance of working in humans. One of the most exciting aspects of organoids is that we can use them to test new therapies in human tissue. Short of a clinical trial, it’s the only way you can achieve this objective.”

The FDA granted an Orphan Drug Designation for further development.

The human organoids also confirmed the findings in mice that molecular movement is critical. The team tested it first on a healthy organoid.

“The dancing molecules spun out all these long neurites on the surface of the organoid but, when we used molecules that had less or no motion, we saw nothing,” Stupp said. “Receptors in neurons and other cells constantly move around. The key innovation in our research is to control the collective motion of more than 100,000 molecules within our nanofibers. By making the molecules move, ‘dance’ or even leap temporarily out of these structures, they are able to connect more effectively with receptors,” he added.

Might the dancing molecules strategy that repairs spinal cord injuries one day also help to heal neurodegenerative diseases, like ALS, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease? Stay tuned.