Better Mitochondrial Replacement: But Why?

The disconnect was striking between the headline of the news release a few days ago – “Improved method for mitochondrial replacement therapy” – and the title of the paper to which it refers – “Towards clinical application of pronuclear transfer to prevent mitochondrial DNA disease.”

The news release reported changes in the experimental protocol for pronuclear transfer (PNT) a proposed way to prevent mitochondrial disease. Pronuclei house the genomes in egg and sperm. PNT places them into human fertilized ova whose nuclei have been removed, but whose mitochondria remain in the cytoplasm. The intent is to fashion fertilized ova missing the mitochondria from a woman who has a mitochondrial mutation, which she’d know from having a child with one of the dozen or so diseases caused by mutations in mitochondrial genes. (Additional conditions that affect mitochondria result from mutations in genes in the nucleus).

The paper, published yesterday online in Nature, is from Mary Herbert and colleagues at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Mitochondrial Research, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom.

It’s a clear, concise report of technically elegant and extensive work, but the elephant in the room looms large: why attempt to replace mitochondria at all?

It’s a clear, concise report of technically elegant and extensive work, but the elephant in the room looms large: why attempt to replace mitochondria at all?

Mitochondria 101

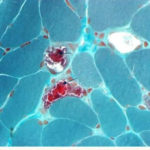

The science behind mitochondrial replacement is complex because DNA in mitochondria is not apportioned in the same way as DNA in the nucleus. A somatic (body) cell has one nucleus housing two genome copies, but it has hundreds to thousands of mitochondria, and each has several copies of its own tiny genome.

In a woman with two variants of a mitochondrial gene, as the mitochondria whittle down from 100,000 to about 100 in her eggs as they mature, the variants aren’t distributed evenly as they would be in the nucleus. As a result, a woman might have a mutation in too few mitochondria to make her sick, yet have a sick child when the developing egg unluckily is dealt many copies of the mutation.

Siblings may be affected to vastly different degrees. Plus, in an individual, mitochondria in one cell type may have many copies of the mutation while other cell types have hardly any. A child with the profound fatigue of a mitochondrial disease reflecting the abundant mitochondria in her muscle cells might have white blood cells that do not indicate the disease. Diagnosis may be tricky.

My posts here and at Medscape Medical News covering a meeting in 2014 of FDA’s Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee discuss the details of mitochondrial replacement.

Timing is Everything

In the new work, the researchers improve PNT by intervening earlier, just as the egg completes the second meiotic division and the pronuclei are visible. (An egg does not actually finish meiosis, the form of cell division that results in sex cells, until it is fertilized. Developing sperm do so every few months.)

In past experiments on mice and abnormal human fertilized ova that didn’t work so well, the pronuclei were sent into the vacated fertilized egg later, right before the first mitotic division takes one cell to two and the pronuclei disappear. The new approach is a little like doing something to an engaged couple versus doing it after they’re married. (I’m planning a wedding right now, forgive the analogy). And the fertilized ova in the current work were normal.

Shifting the timeframe ups the odds that manipulated fertilized ova reach the hollow-ball blastocyst stage, at day 5. The smear of cells on the interior face of the ball, called the inner cell mass, grows, folds, and contorts to become the embryo. The outside cells develop into supportive membranes. With the earlier intervention, the inner cell mass is less likely to lose or gain a chromosome as its cells divide, or to veer significantly from normal gene expression.

The researchers examined 131 normal fertilized ova from 30 donors. Thirty of the 131 were untouched controls, 21 had their own pronuclei drawn in and out to mimic the effect of any manipulation, and 80 underwent the full test – receiving two pronuclei.

Results were impressive: 79% of the 80 treated blastocysts received less than 2% of the mitochondrial DNA from the female pronucleus donor. This is below the 18% threshold for developing symptoms and transmission to offspring. “We conclude that PNT has the potential to reduce the risk of mtDNA disease, but it may not guarantee prevention,” the researchers write. Yes, it looks like it could indeed work.

But Is It Necessary?

Pronuclear transfer into fertilized ova sounds like a huge effort, and I can’t help but think of reasons not to pursue it:

• There are other ways to avoid mitochondrial disease: IVF with a donor egg. Adopt.

• Mitochondrial replacement doesn’t improve the health of a living person, as patients pointed out to the FDA.

• PNT is fascinating and a technological feat, but isn’t it basic cell biology research and not (yet) a therapy?

• Joining two nuclear genomes with a mitochondrial genome from a third person creates a “3-parent” embryo. That doesn’t bother me, because the mitochondrial genome is a mere 16,569 DNA nucleotides compared to the 3 billion or so in the nucleus, and DNA is DNA. The “3-parent” label that has bioethicists in an uproar implies that parental contributions are equal.

• Experimenting on human fertilized ova, especially normal ones, is controversial. It too doesn’t bother me, because we’re talking about cells, not babies. But hasn’t the work by these researchers and others using abnormal fertilized ova implied the inappropriateness of using normal ones? I respect that to people who consider life to begin at conception, the intervention would be horrifying.

The Apples and Oranges of Biotechnology

This may be the first time I’ve not fully supported a biotechnology. I’m reminded of the several-year debate that enveloped sequencing the first human genomes. Among the reasons I thought valid — to find cures for genetic disease and cancer, to learn about the effects of radiation on DNA — was the Mount Everest argument: to sequence “the” human genome just because it was there, and we could.

CRISPR and other genome editing technologies are currently under fire because they, too, replace something in nature, a stretch of DNA or RNA. But genome editing might be applied to somatic cells to treat disease in existing people; editing the human germline is a different matter, evoking the same objection as to mitochondrial replacement. Don’t mess with fertilized ova or embryos. The existing and widely-used combo of in vitro fertilization (IVF) and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) doesn’t manipulate embryos, it just selects those with the best chances.

I also understand that all sorts of unrealized benefits come from basic research, such as the space program and sequencing genomes. But I think with mitochondrial replacement, we have a Mt. Everest situation.

There’s also the apples-to-oranges arguments of more profound medical needs, the disturbing triaging of who is more important.

Postnatal versus prenatal.

Developed nation versus developing.

Rare disease versus common infection.

If funds were limited, I think they would perhaps have a greater impact if directed towards understanding zika virus infection, difficult-to-conquer cancers such as glioblastoma, the triad of HIV/TB/malaria that won’t go away, diabetes, gun violence, the list goes on. Ethically questionable, costly and difficult technology, to provide more children when so many already born are in need of families, just doesn’t make sense to me. I can’t even see how the unusual situation of sending pairs of pronuclei into vacated fertilized eggs will reveal anything new about early human development.

I have healthy children, so perhaps I am being insensitive to the plight of having a biological child with a mitochondrial disease and desiring more biological children free of the condition. But as long as there are alternative ways to have healthy children, against the backdrop of powerful objections, I think that efforts to manipulate mitochondria, unless directed at developing a treatment for patients, should stop.

“There are other ways to avoid mitochondrial disease: IVF with a donor egg. Adopt.”

Hard to imagine a more callous response.

So you’re telling a woman who wants to bear a child _from her own ova_ that she shouldn’t do so, just because you have some unarticulated opposition to mitochondrial replacement?

Dr Lewis spend a good amount of effort explaining that certain issues “don’t bother” her, but then she adopts the positions that would seem to only be adopted by a person who was “bothered” by genetic manipulation. Having three parents? Who cares?? When has anybody ever cared about the source of mitochondrial DNA?

[…] Source: Better Mitochondrial Replacement: But Why? […]

I’m just making a suggestion — that adoption is an alternative to undergoing a manipulation to have a biological child. Trying to get a conversation started on an intriguing new paper. I attempted to keep the emotion out of the discussion and present facts from what I know about the biology of mitochondria, while respecting others’ opinions. There has in fact been quite a bit of discussion about the idea of a 3-parent embryo resulting from mitochondrial manipulation. I’ve reported on it before and am just continuing the discussion. Some people apparently do care about the source of mitochondrial DNA.

I think that it doesn’t really matter that this technique is not all that necessary. It is worth doing because it expands knowledge, and doesn’t hurt anything. As you know, advances don’t stay put in the exact realm they were devised for, and so I think this is maybe not the most practical advance, but it is a scientific advance that adds to what we know and what we can do without any clear downside. So I say – bravo!

It is an amazing accomplishment, and a great paper, and it’s true, we can never know when knowledge can be applied. Thanks for sharing.

I think this is an amazing accomplishment, but agree that it is research and not appropriate to give potentially false hope to families at risk of mitochondrial disease. Two issues you have raised with this example, should we do it because we can, and how research slips into clinical practice without the evidence that is supposed to be the mainstay of conventional medicine, need a lot more public discussion. There are many clinical practices that have become established and routine in a high risk population where there may be evidence, slipping into general use on low risk populations, where there is little or no evidence.