Clues to combatting a devastating disease can come from identifying people who have gene variants – mutations – that protect them, by…

How Breast Cancer Reunited Six High School Friends

In recognition of Breast Cancer Awareness month, I am republishing this essay written on the eve of the pandemic. It’s an intriguing perspective: in a matter of weeks, everyone worried about survival, not just those of us with cancer and other life-threatening or altering conditions. I’m happy to report that all of us who have faced breast cancer are doing well!

January 16, 2020

Four of the six of us from my high school inner circle have had breast cancer over the past two years. And that has me wondering.

Did a shared environmental exposure, stamped onto our shared Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, during that critical period in our lives set the stage for cancer decades later? The timing and cancer subtypes suggest to me, the biologist in the group, that the answer could be yes. But I’m flummoxed.

An Illustrious High School

The long walk to James Madison High School began every weekday morning with me. I’d pick up my neighbor Amy, then Randy two blocks over, then across the street and a few steps to Wendy. We’d turn right onto Quentin Road to meet Tobie, then dip into East 18th Street, to get Bess in her rambling Victorian that was to the rest of us, from smaller homes and apartments, a mansion. It was the epicenter of the best parties.

We began tenth grade at Madison shortly after Woodstock and graduated as the class of 1972. Famous alumni include Carole King, Bernie Sanders, Chuck Schumer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Judge Judy Scheindlin, Martin Landau, and Chris Rock (See “How One ‘Ordinary’ Brooklyn High School Produced Six Nobel Laureates, a Supreme Court Justice, and Three Senators.” )

We began tenth grade at Madison shortly after Woodstock and graduated as the class of 1972. Famous alumni include Carole King, Bernie Sanders, Chuck Schumer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Judge Judy Scheindlin, Martin Landau, and Chris Rock (See “How One ‘Ordinary’ Brooklyn High School Produced Six Nobel Laureates, a Supreme Court Justice, and Three Senators.” )

Our only brush-up with celebrity was Fran Schumer, sister of Chuck, who was an exalted senior and valedictorian when we started. She wrote a compelling piece for the Harvard Crimson in 1973, about the race riots at Madison the fall after we graduated. For what it’s worth, our school’s history wasn’t always something to be proud of.

Silence Like a Cancer Grows

Flash forward.

I was diagnosed with breast cancer in late 2017.

Wendy in late 2018.

Amy in June 2019.

Bess’s mom died of BC in October, 2019.

And Tobie was just diagnosed, late 2019.

In each of us, one cell in a milk duct went rogue, dividing faster than the cells around it, slowly building into a nubbin of clinging cells, like our group grew every morning as Ricki picked up Amy and we picked up Randy, then Wendy, then Tobie, then Bess. Was our ritual walk to school a metaphor of what was to come?

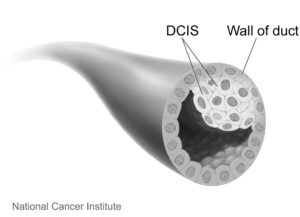

Cancers take years, even decades, to grow. It isn’t a steady path. Some cancer cells become quiescent and hide, then mutate anew into a frenzy. For two of us the cancer was DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ), still in a milk duct. For the other two, it had spilled out, dubbed IDC (invasive ductal carcinoma).

Our cancers were early. Small. Fixable. But terrifying.

When a suspicious, routine mammogram catapults you through the maze of more scans, biopsies, and then a zillion treatment choices, you have to become expert in interpreting the nuances of a pathology report – or find someone who is. Listen to doctors, do research, then finally decide.

When a suspicious, routine mammogram catapults you through the maze of more scans, biopsies, and then a zillion treatment choices, you have to become expert in interpreting the nuances of a pathology report – or find someone who is. Listen to doctors, do research, then finally decide.

I took the most drastic action – I had reason to believe my case was worse than the others.

Unlike the errant cells of my high school buddies, mine were grade 3 – dividing as often as they could – and devoid of the hormone (estrogen and progesterone) receptors that festoon healthy breast cells. Only 14% of new breast cancers are hormone receptor negative. If my cells were also missing a receptor called HER2, which is only tested for in invasive cancer, I’d be triple negative, an aggressive subtype. Receptor-blockers are used to treat “ER+” and “PR+” cancers.

But I’d have chosen mastectomy no matter what the grade and receptor findings were, because I couldn’t shake the images of my mother’s metastatic breast cancer. That was 20 years ago, before the targeted treatments that are greatly extending survival today. Back then, going 5 years without recurrence elicited the other “c” word – cure. We didn’t yet know that breast cancer cells can hide. My mom’s came back more than a decade later.

Look at Mother Nature On the Run, In The 1970s

Genetic testing indicates that none of us inherited a pathogenic variant of a risk gene, like BRCA1 and 2, ATM, CHEK2, TP53, BARD1, RAD51, or dozens of others. (I had 108 genes analyzed.) But these tests are for the mutations present from conception, not the much more common ones that happen in breast cells as the beat of cell division goes on. Something in the air might trigger these.

But what? I tried to drill down into what we did back then.

Was it pot? Unfortunately the adage “if you don’t remember the ’60s you weren’t really there” is somewhat true, because Wendy and I have rather hazy recollections. But Randy remembers who did and didn’t smoke a lot of pot because she didn’t. Tobie dabbled, and Amy only tried it later. I seem to remember Bess of party central being in the group with Wendy and myself.

Wendy came up with the subway hypothesis. It made sense, at first.

The tiny scrap of a backyard in her row house on East 16th Street was literally a stone’s throw from the elevated D train (now the B), which barreled past a few times an hour, all the time. Did carcinogens waft through her kitchen windows onto the plasticine grilled cheeses her mom made for us?

The tiny scrap of a backyard in her row house on East 16th Street was literally a stone’s throw from the elevated D train (now the B), which barreled past a few times an hour, all the time. Did carcinogens waft through her kitchen windows onto the plasticine grilled cheeses her mom made for us?

I hit the medical literature.

Google Scholar quickly belched out a 1991 study of the effects of whole-body vibration on New York City subway conductors. Nope.

Another study probed exposure to noxious hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide inside a Volkswagon and a subway car circa mid-1990s Berlin. The car was a hotbed of benzene but the subway car not so bad. Similarly, particulate matter inhaled on the subway was less of a threat in Guangzhou, China, than walking, biking, or taking the bus.

A 2008 study exonerated the Stockholm subway from causing lung cancer in men. And a year later, another scintillating investigation revealed spiked markers of inflammation in 20 healthy folks who’d volunteered to inhale large particulates in a subway for 2 hours.

So, I don’t think Wendy’s toxic backyard caused our cancers.

Was it something in the hallowed halls of James Madison High School?

What about food?

Was it the 1960s version of a food truck outside the school, in which a weird man would surreptitiously slip hot dogs inside mushy knishes? I seem to be the only one to recall that.

We can eliminate egg creams, which we all drank in the candy store at East 18th Street and Kings Highway. (For the uninformed, the recipe is seltzer, chocolate syrup, and a splash of milk.) So they’re innocuous, as is the ice cream we all ate at the Carvel across the street from the candy store.

We can eliminate egg creams, which we all drank in the candy store at East 18th Street and Kings Highway. (For the uninformed, the recipe is seltzer, chocolate syrup, and a splash of milk.) So they’re innocuous, as is the ice cream we all ate at the Carvel across the street from the candy store.

Randy of the sharp memory ventured the hypothesis that she inadvertently consumed something that might have protected her. “Flying saucers, parfaits, cherry bonnets, chocolate bonnets! Carvel was next door to Candy Masters where I supported the owner with my purchases of Turkish pistachios. I’m still eating them in ridiculous amounts – maybe that’s why I’m cancer free!”

Sorry Randy. Wendy to this day eats pistachios obsessively, and I like them too.

Was it the sun?

At the beach, a short bike ride’s journey, five of us actually used reflectors (foil-lined contraptions like those things you put on dogs who’ve had dental work) to concentrate the carcinogenic ultraviolet solar radiation onto our whiter shade of pale, baby-oil-soaked, young faces. We took this idiotic action for many days each summer, probably mutating our delicate skin cells and who knows what else.

How about exposure to agricultural pesticides? For a time, studies linked women who lived on Long Island close to hazardous waste sites spewing organochlorine pesticides like DDT to breast cancer, but a more recent report questions that connection.

Might Brooklyn, which is technically part of Long Island, have introduced other exposures? Amy points out that some of the houses and apartment buildings in Brooklyn, like the famous brownstones and six-story behemoths, are more than a century old. James Madison High School, on Bedford Avenue, was built in 1925, but some brownstones date from the mid-nineteenth century. Brownstone is iron-rich sandstone. But I doubt it’s carcinogenic or all those people in the newly-gentrified sections of the borough wouldn’t be paying millions for them.

Might Brooklyn, which is technically part of Long Island, have introduced other exposures? Amy points out that some of the houses and apartment buildings in Brooklyn, like the famous brownstones and six-story behemoths, are more than a century old. James Madison High School, on Bedford Avenue, was built in 1925, but some brownstones date from the mid-nineteenth century. Brownstone is iron-rich sandstone. But I doubt it’s carcinogenic or all those people in the newly-gentrified sections of the borough wouldn’t be paying millions for them.

You’ve Got a Friend

We’ll probably never figure out what caused four of the six of us to develop similar breast cancers that showed up within a two-year span. But in the meantime, something wonderful has come from the experience. Renewed friendship.

Facebook facilitated our initial reconnection, as we fleetingly followed each other’s lives. We‘d lost touch, except for a pair here and there, and a very rare get together of subsets, including a few others who were just outside of our small circle of friends because they didn’t live on our route to school.

But when the first suspicious mammogram appears, or a biopsy result is bad, social media, texts, and emails no longer suffice.

And so we began to talk to each other, like we used to do on the phone for hours every day, even after being together on that long walk to and back from James Madison High School. The newly diagnosed, in shock, listened, while the veterans explained the long and winding road of looming medical options, sometimes carefully keeping out disturbing details.

After treatment, we sent notes, books, flowers, gift cards. I recently mailed Tobie a stuffed large intestine I’d gotten from the Mutter Museum of medical oddities in Philadelphia, because tucked in my armpit, it had helped me sleep after the lymph node probing, more soothing than C-shaped neck pillows. (The Museum is famed for its 6-foot distended human colon.)

Wendy brought me a cheery stuffed hippo and knishes. We watched the special Bandersnatch episode of Black Mirror and played the game of choosing a story path and alternate endings, which inspired my DNA Science post from exactly a year ago comparing the game to a journey with breast cancer.

Randy, crochet designer extraordinaire, made me knitted knockers. Since 2007, a nationwide army of talented volunteers has made these soft boob replacements and donated them to women with BC. One of my knitted knockers launched itself from the flatitude of my chest during my daughter’s bridal shower, but aside from that, they’re a wonderful alternative to the torture devices otherwise known as “breast forms,” although even those are better than what my mother had. OK, TMI.

Tobie was and is the clown. She could always make us laugh, even in the immediate aftermath of hearing what no woman wants to hear. And it was she who suggested, before her surgery just last week when we’d all begun madly texting, that we tell our story. So, here I am.

It’s difficult and counterintuitive to look for a bright side to cancer. But I think we are all comforted by our reconnection. Carry on! (The last of the ’60s/’70s song titles and lyrics embedded in this post.)